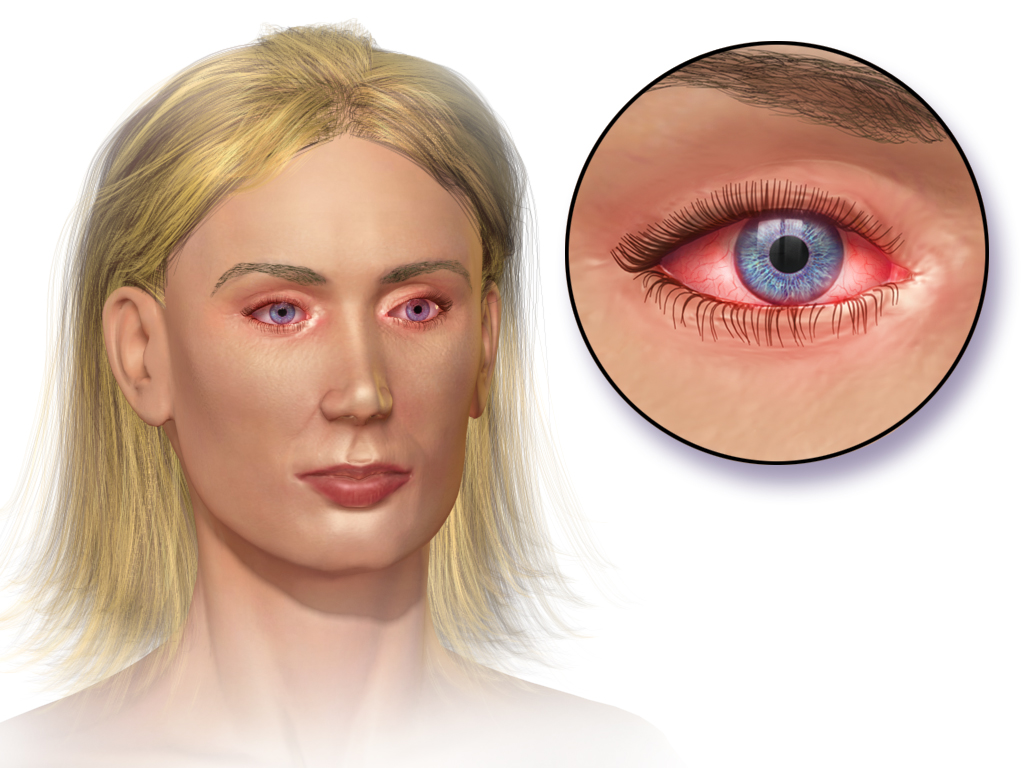

Red Eye

Last updated August 5, 2025

Medical information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

See our Terms & Conditions and Consent for Telemedicine for details.

Overview

“Red eye” is a broad, everyday term that simply describes an eye whose white sclera looks pink, blood-shot, or uniformly red. The color change happens because surface blood vessels become enlarged or leaky when the eye is irritated, inflamed, infected, or injured. Most cases are mild and clear within a week, but redness can also signal serious problems that threaten sight, such as acute glaucoma or a corneal ulcer. Because dozens of conditions can lead to redness—from dry eye and allergies to trauma and viral infections—context and accompanying symptoms matter. When redness is paired with pain, vision changes, light sensitivity, thick discharge, or recent eye surgery, experts advise prompt medical evaluation.

Although red eye often looks dramatic, remember that many minor causes respond well to simple measures like lubricating drops, cool compresses, and a day or two of rest away from contact lenses. Still, if you are unsure, an eye-care professional can quickly differentiate a harmless irritation from an emergency.

Symptoms

The hallmark sign is a pink or crimson tinge to the normally white sclera. Additional clues help narrow the diagnosis:

- Irritation or gritty feeling suggests dry eye, blepharitis, or allergy.

- Watery discharge and itching point to allergic conjunctivitis.

- Thick, yellow-green discharge is more typical of bacterial infection.

- Blurred vision, halos around lights, or eye pain hint at deeper inflammation like uveitis or keratitis.

- Sudden, bright red patch with no pain is likely a subconjunctival hemorrhage—alarming in appearance but usually harmless.

Systemic symptoms such as fever, joint pain, or skin rash may indicate a viral illness or autoimmune disorder that also involves the eye.

Causes and Risk Factors

Common culprits include:

- Conjunctivitis (pink eye)—viral, bacterial, or allergic.

- Dry-eye disease and blepharitis that inflame the ocular surface.

- Contact-lens overwear, poor hygiene, or sleeping in lenses.

- Trauma or a foreign body scratching the cornea.

- Environmental irritants—smoke, chlorine, or windy, dusty air.

Risk rises if you wear contact lenses, have seasonal allergies, work in dusty settings, share personal eye products, or have systemic autoimmune diseases. Age matters too—children pick up contagious viral conjunctivitis easily, while adults may see redness from dry eye or ocular rosacea.

Enter your details in the following fields to calculate your risk

Risk Level

Recommendation

Diagnosis

An eye-care provider will review symptom timing, exposures, contact-lens habits, and any accompanying pain or vision loss. A slit-lamp exam lets the clinician inspect the cornea, anterior chamber, and eyelids under magnification. Fluorescein dye may highlight abrasions or ulcers, and intraocular pressure is checked to rule out acute glaucoma. If infection is severe or recurrent, a swab of ocular discharge can be cultured, and in stubborn cases blood tests for autoimmune markers are ordered.

Rapid triage is critical: danger signs include severe pain, photophobia, corneal haze, pupil irregularity, or an inability to keep the eye open—all require same-day ophthalmology referral.

Treatment and Management

Therapy depends on the root cause:

- Lubricating artificial tears soothe most irritative redness and are safe to use frequently.

- Cold compresses and oral antihistamines ease allergic conjunctivitis, while prescription topical antihistamine–mast-cell stabilizer drops provide faster relief.

- Topical antibiotics target bacterial conjunctivitis; dosing is usually every 4–6 hours for 5-7 days.

- Contact-lens–related keratitis requires immediate discontinuation of lenses and may need fortified antibiotic drops every hour.

- Subconjunctival hemorrhage typically needs no treatment beyond reassurance.

Non-prescription “get-the-red-out” vasoconstrictor drops give temporary cosmetic improvement but can cause rebound redness; use them sparingly. Never place steroid drops unless prescribed—misuse can worsen infections and raise eye pressure.

Living with Red Eye and Prevention

You can lower your risk of recurrent redness by following these habits:

- Wash hands frequently and avoid touching or rubbing the eyes.

- Remove makeup nightly and replace eye cosmetics every three months.

- Follow the “20-20-20 rule” (look 20 feet away for 20 seconds every 20 minutes) to reduce digital-screen dryness.

- Keep contact lenses clean; never sleep in daily-wear lenses.

- Use protective eyewear during sports, yard work, or chemical use.

- Stay hydrated and run a humidifier if indoor air is dry.

If you develop chronic redness, your provider may suggest omega-3 supplements, eyelid-scrub routines, or punctal plugs to boost tear film quality.

Latest Research & Developments

Ongoing studies funded by the National Eye Institute (NEI) are exploring nanobody-based antiviral drops, gene therapies for inherited conjunctival inflammation, and smart contact lenses that monitor corneal oxygenation in real time. Researchers are also repurposing well-known blood-pressure medications to dampen ocular surface inflammation and testing topical probiotics to rebalance the eyelid microbiome.

Early-phase clinical trials now underway examine messenger-RNA eye drops to boost natural tear production in patients with chronic dry eye, a leading driver of redness. Participation in these trials may provide access to innovative treatments years before general release.

Next Steps

Best specialist to see: an ophthalmologist—ideally one comfortable with urgent anterior-segment care—can evaluate the full spectrum of red-eye causes, perform in-office microscopy, and start sight-saving treatment the same day if needed.

How to schedule: Start with your primary-care doctor or optometrist for a quick triage; they can fax a referral, which helps insurance approvals. However, most ophthalmology offices also allow self-referral—call and state you have sudden eye redness plus any “red-flag” symptoms (pain, vision change, light sensitivity) for expedited slots. If after hours, head to an emergency department linked to an eye institute.

Need help locating a provider? Use major academic-center directories or the Cleveland Clinic and Mayo Clinic scheduling lines. When in doubt, err on the side of being seen; untreated eye emergencies can worsen within hours.

Trusted Providers for Red Eye

Dr. Connie Wu

Specialty

Glaucoma

Education

The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Dr. Dane Slentz

Specialty

Oculoplastics

Education

Oculoplastics

Dr. Emily Eton

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Harvard Medical School

Dr. Emily Schehlein

Specialty

Glaucoma

Education

Glaucoma

Dr. Grayson Armstrong

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Ophthalmology

Dr. Jose Davila

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Retina/Vitreous Surgery

Dr. Karen Chen

Specialty

Glaucoma

Education

Glaucoma

Dr. Levi Kanu

Specialty

Cornea and External Disease

Education

Cornea and External Disease

Dr. Nicholas Carducci

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine