Conjunctivitis

also known as Pink Eye

Last updated July 28, 2025

Medical information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

See our Terms & Conditions and Consent for Telemedicine for details.

Overview

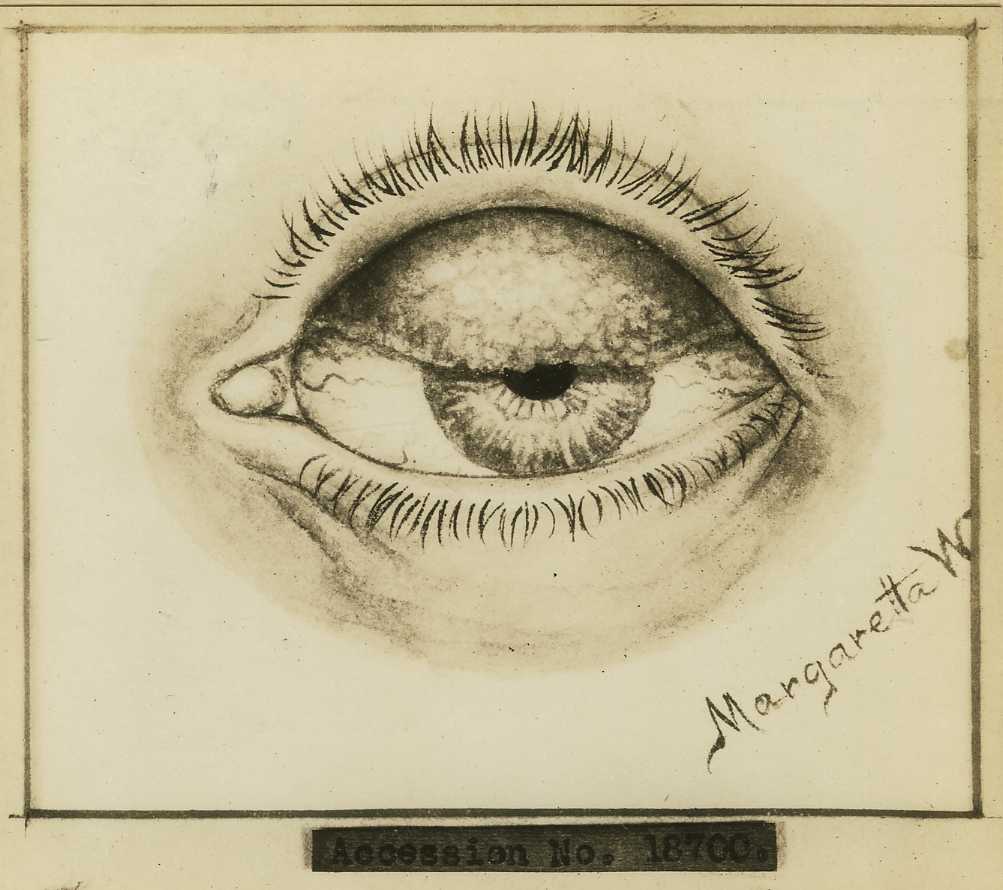

Conjunctivitis—better known as “pink eye”—is an inflammation of the thin, transparent membrane covering the white of the eye and the inner eyelids. When the conjunctiva becomes irritated or infected, tiny blood vessels swell and turn the sclera pink or red. Most cases are mild and resolve without lasting damage, yet pink eye accounts for roughly 3 million missed school or work days in the United States each year.1 Although viruses cause the majority of infections, bacteria, allergens, chemicals, and even over‑worn contact lenses can also provoke inflammation.2 Vision‑threatening complications are rare, but any severe pain, light sensitivity, or blurred vision should prompt urgent evaluation. Good hygiene and prompt identification of the trigger are the keys to keeping pink eye from spreading and to protecting long‑term eye health.

Symptoms

- Red or pink sclera from dilated surface vessels

- Watery, mucous, or pus‑like discharge—clear for viral/allergic disease, thick yellow‑green for bacterial

- Grittiness, itching, or burning that makes patients want to rub the eyes

- Eyelid crusting that may seal lids shut on waking

- Mild lid swelling and tearing that can blur vision temporarily

Less typical but serious warning signs include marked light sensitivity, severe pain, a blister‑like rash on the eyelid, or noticeable vision loss—features that suggest herpes keratitis, iritis, or acute glaucoma. Anyone experiencing those “red‑flag” symptoms should seek care the same day. In uncomplicated viral pink eye, irritation peaks at 3–5 days and clears within two weeks.4 The Mayo Clinic notes that allergic cases often bring intense itch, while bacterial infections more commonly glue the lashes together with sticky pus.3

Causes and Risk Factors

Causes

- Viral (≈70 %) — usually adenovirus but also enteroviruses, herpes simplex, or SARS‑CoV‑2.5

- Bacterial (≈20 %) — S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae; N. gonorrhoeae requires immediate systemic therapy.13

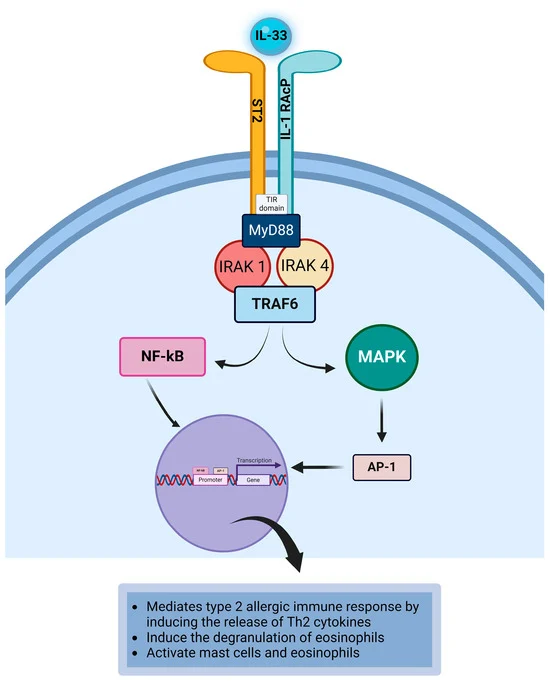

- Allergic — IgE‑mediated reaction to pollen, pet dander, or dust mites.

- Irritant/toxic — chlorine, smoke, chemical splashes, contact‑lens overwear.

Risk factors

- Close contact in schools, day‑care, or dormitories

- Recent upper‑respiratory infection or COVID‑19 exposure

- Seasonal allergies or severe atopy

- Sleeping in contact lenses or poor lens hygiene

- Immunosuppression, diabetes, or ocular surface disease

- Newborn passage through an infected birth canal

Understanding the underlying trigger guides both treatment and infection‑control advice.

Pink Eye Risk Snapshot

Enter your details in the following fields to calculate your risk

Risk Level

Recommendation

Diagnosis

Most cases are diagnosed clinically. A provider will confirm visual acuity, inspect the pattern of redness, and perform fluorescein staining to rule out corneal ulcers. Tender pre‑auricular lymph nodes point toward viral infection, while copious purulent discharge hints at bacteria. Cultures or rapid adenovirus tests are reserved for severe, recurrent, neonatal, or contact‑lens‑related cases. The American Academy of Ophthalmology’s 2023 Preferred Practice Pattern stresses quick referral for suspected herpes keratitis, iritis, or acute angle‑closure glaucoma because delays can cost vision.6

Treatment and Management

Supportive care for all types: cool compresses, preservative‑free artificial tears, and strict hand‑washing.

- Viral: usually self‑limited in 7–14 days; lubricants and chilled saline ease discomfort. Antivirals are reserved for herpetic disease.7

- Bacterial: broad‑spectrum antibiotic drops (e.g., polymyxin‑trimethoprim, erythromycin) shorten illness by 1–2 days and curb contagiousness. Contact‑lens wearers need fluoroquinolones.

- Allergic: dual‑action antihistamine/mast‑cell stabilizer drops and oral antihistamines control itch; severe cases may need a short steroid taper under supervision.8

- Chemical / irritant: immediate irrigation followed by lubricant drops; topical steroids only with ophthalmologist oversight.

Living with Conjunctivitis and Prevention

Infectious pink eye is extremely contagious but also highly preventable. Simple steps—frequent hand‑washing, avoiding eye‑rubbing, and not sharing towels, cosmetics, or eye drops—dramatically cut spread.9 Students or workers with viral or purulent bacterial conjunctivitis should stay home until tearing subsides or 24 hours after starting antibiotics. Contact‑lens wearers should switch to glasses until redness resolves. Regular lens cleaning, timely lens replacement, and sleeping without lenses reduce recurrences.12 People with chronic allergies benefit from HEPA filters, allergen covers, and pre‑seasonal use of antihistamine drops.

Latest Research & Developments

- COVID‑19 “Arcturus” variant: The XBB.1.16 subvariant has been linked to itchy, sticky eyes in children, prompting updated triage protocols that include COVID testing when pink eye appears with fever or cough.10

- Reactive‑aldehyde species inhibitor (reproxalap): After a second complete‑response letter in April 2025, the FDA again declined to approve Aldeyra’s topical therapy, citing insufficient efficacy data.11

- Point‑of‑care adenovirus tests: New CLIA‑waived antigen assays deliver results in under 15 minutes, helping clinicians avoid unnecessary antibiotics.

- Tele‑ophthalmology: Studies presented at recent AAO meetings show smartphone photos correctly classify conjunctivitis subtype in over 80 % of cases when reviewed remotely by cornea specialists.

Recently Published in Peer-Reviewed Journals

The British journal of ophthalmology

June 15, 2025

International corneal and ocular surface disease dataset for electronic health records.

Ting DSJ, Kaye S, Rauz S, et al.

BMC ophthalmology

May 7, 2025

Treatment of corneoscleral mixed hemangioma by intrastromal lenticule transplantation in a case of xeroderma pigmentosum: a case report.

Wang Y, Cai L, Feng H, et al.

BMC ophthalmology

April 17, 2025

The therapeutic effect of IPL on children with refractory seasonal allergic conjunctivitis.

Jiang J, Yang X, Du F, et al.

Next Steps

If redness, discharge, or discomfort lasts more than a few days—or if you experience severe pain, blurred vision, or light sensitivity—schedule an evaluation with a comprehensive ophthalmologist or cornea/external disease specialist. You can ask your primary‑care doctor for a referral, check your vision‑insurance directory, or contact your local medical society. Typical wait times range from same‑day for urgent symptoms to a week for routine follow‑up. Many offices now offer tele‑triage for photograph review before an in‑person visit. If you’d like personalized help connecting to the right specialist, you can start that process directly through Kerbside’s platform.

Trusted Providers for Conjunctivitis

Dr. Connie Wu

Specialty

Glaucoma

Education

The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Dr. Dane Slentz

Specialty

Oculoplastics

Education

Oculoplastics

Dr. Emily Eton

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Harvard Medical School

Dr. Emily Schehlein

Specialty

Glaucoma

Education

Glaucoma

Dr. Grayson Armstrong

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Ophthalmology

Dr. Jose Davila

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Retina/Vitreous Surgery

Dr. Karen Chen

Specialty

Glaucoma

Education

Glaucoma

Dr. Levi Kanu

Specialty

Cornea and External Disease

Education

Cornea and External Disease

Dr. Nicholas Carducci

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine