Corneal Ulcer

also known as Keratitis

Last updated July 28, 2025

Medical information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

See our Terms & Conditions and Consent for Telemedicine for details.

Overview

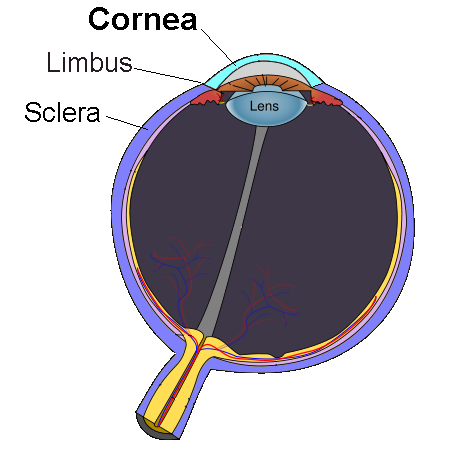

A corneal ulcer is an open sore that forms in the clear front window of your eye (the cornea). Because that window focuses incoming light, even a tiny ulcer can blur vision or lead to permanent scarring if treatment is delayed. Most ulcers begin when germs—bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites—invade the cornea after a scratch, contact-lens mishap, or severe dry eye. Your immune system rushes in, inflaming nearby tissue and making blood vessels leak, which is why the eye often looks red and feels painful. Ophthalmologists consider any suspected corneal ulcer an emergency: sight-threatening complications can develop in hours, not days. The good news is that with prompt medical care, many people heal completely and avoid long-term vision loss.

Remember, redness alone is not always alarming, but redness plus pain, light-sensitivity, or decreased vision should trigger a same-day exam by an eye-care professional.

Symptoms

Classic warning signs include:

- Eye pain or a gritty, foreign-body sensation

- Redness that often worsens quickly

- Tearing or thick, sometimes yellow-green discharge

- Blurry or hazy vision; objects may look as if they are behind frosted glass

- Light sensitivity (photophobia); bright light can feel unbearable

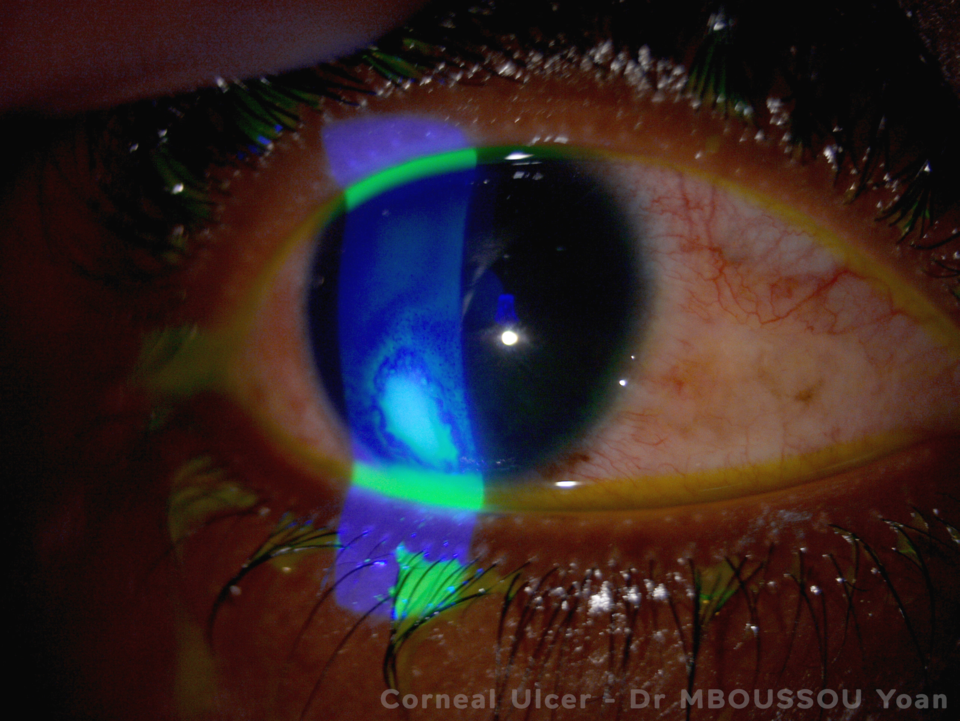

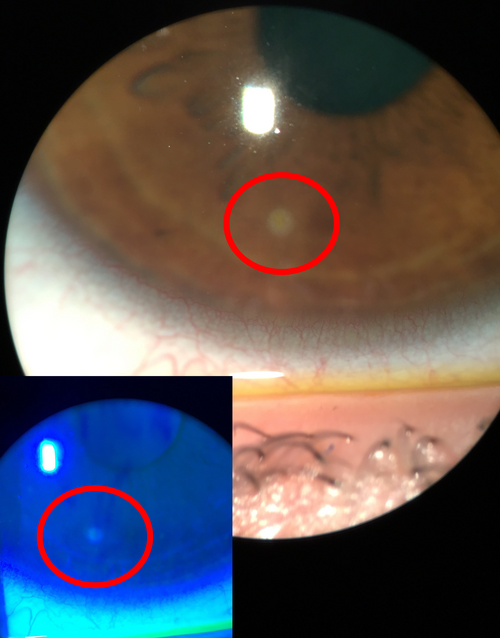

- Whitish or gray spot on the cornea—large ulcers can be seen in the mirror

Some patients also notice eyelid swelling or feel that the eyelid cannot fully open. If pain suddenly lessens, it may indicate nerve damage rather than improvement—another reason not to self-diagnose.

Causes and Risk Factors

Corneal ulcers usually start with an infection:

- Bacterial (most common in contact-lens wearers)

- Fungal (often after eye trauma with plant material or prolonged steroid-drop use)

- Viral (herpes simplex or herpes zoster)

- Parasitic (Acanthamoeba, classically linked to swimming or showering in contact lenses)

Key risk enhancers include:

- Sleeping or swimming in soft contact lenses

- Corneal scratches, foreign bodies, or chemical burns

- Chronic dry-eye disease or eyelid inflammation (blepharitis)

- Topical steroid drops that suppress local immunity

- Systemic immunosuppression (diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, chemotherapy)

In a landmark review of contact-lens–related infections, researchers highlighted overnight lens wear as the single most modifiable risk factor for microbial keratitis and ulceration.

Enter your details in the following fields to calculate your risk

Risk Level

Recommendation

Diagnosis

An ophthalmologist begins with a detailed history (symptom timeline, contact-lens habits, recent trauma) followed by a slit-lamp examination. Special blue light and fluorescein dye highlight the ulcer’s borders and depth. Additional tests can include:

- Corneal scrapings for Gram stain, culture, or PCR to pinpoint the organism

- Confocal microscopy for suspected Acanthamoeba

- Anterior-segment OCT imaging to monitor healing depth

- Intraocular pressure measurement to rule out secondary glaucoma

Because delayed treatment worsens outcomes, most eye doctors start broad-spectrum antibiotic drops immediately after cultures are taken—even before lab results return.

Treatment and Management

Therapy is tailored to the underlying germ and the ulcer’s size and location:

- Fortified antibiotic drops (e.g., vancomycin + ceftazidime) every 15–60 minutes for severe bacterial ulcers

- Topical antifungals such as natamycin 5% for filamentous fungi or voriconazole for yeast infections

- Topical antivirals (ganciclovir gel) ± oral acyclovir for herpetic ulcers

- Cycloplegic drops (e.g., homatropine) to relieve pain and prevent synechiae

- Oral pain relief and strict activity modification—no contact lenses until cleared

- Corneal transplant (penetrating keratoplasty) when medical therapy fails or scarring blocks the visual axis

Do not use leftover steroid drops unless your ophthalmologist specifically prescribes them; steroids can turn a mild ulcer into a rapidly spreading melt.

Living with Corneal Ulcer and Prevention

Once the ulcer heals, regular follow-up helps detect recurrent infection or elevated eye pressure. To lower your risk of ever facing another ulcer:

- Adopt “healthy contact-lens habits”: wash hands, use fresh solution, rub-and-rinse lenses, replace cases every 3 months, and remove lenses before sleeping or swimming.

- Protect your eyes with safety goggles when using yard equipment or working with chemicals.

- Treat dry eye and blepharitis with warm compresses, lid scrubs, and lubricating drops.

- Keep follow-up appointments; early detection of tiny surface defects prevents big problems.

According to the CDC, meticulous lens hygiene and avoiding overnight wear could prevent the majority of contact-lens–related corneal infections reported each year.

Latest Research & Developments

Scientists are tackling corneal ulcers on several fronts:

- Drug-eluting contact lenses that slowly release antibiotics are in phase 2 trials and may cut dosing from hourly to once daily.

- Pulsed-light collagen cross-linking is being explored as an adjunct to halt tissue “melt” in aggressive bacterial ulcers.

- The National Eye Institute’s Anterior Segment Initiative is funding AI algorithms that use slit-lamp photographs to predict which ulcers need surgery.

- Genome sequencing of Pseudomonas isolates is uncovering new resistance pathways, guiding next-generation topical antibiotics.

An early feasibility study also found that topical bacteriophage therapy cleared multidrug-resistant infections in rabbit models—human trials are expected to begin soon.

Recently Published in Peer-Reviewed Journals

JAMA ophthalmology

July 24, 2025

Steroids and Cross-Linking for Ulcer Treatment: The SCUT II Randomized Clinical Trial.

Prajna NV, Lalitha P, Chandru S, et al.

BMC ophthalmology

July 1, 2025

Monoclonal gammopathy presenting with paraproteinemic keratopathy documented with anterior segment OCT: a case report.

Nouira C, Ghazal W, Panthier C, et al.

Investigative ophthalmology & visual science

July 1, 2025

Hyperglycemia-Suppressed Acod1 Expression Contributes to Innate Immune Deficiency in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Keratitis.

Gao N, Me R, Singh S, et al.

Next Steps

Best specialist to see: a cornea fellowship-trained ophthalmologist. These eye surgeons have the microscopes, drug sets, and surgical skill to manage even the most complex ulcers.

How to schedule: • Ask your primary-care doctor or optometrist for an urgent referral—most insurers approve same-day ophthalmology visits for acute eye pain.

• If you cannot get a quick appointment, call a large eye-care center directly and state, “I have severe eye pain and blurred vision; my doctor suspects a corneal ulcer.” Clinics keep emergency slots for such calls.

• After hours, go to an emergency department attached to a teaching hospital; they can page the on-call ophthalmologist.

Once your eye is stabilized, long-term follow-up with the same cornea specialist helps track scar formation and decide whether vision-restoring surgery (such as a corneal transplant or specialty contact lens fitting) is needed.