Uveitis

also known as Eye Inflammation

Last updated July 31, 2025

Medical information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

See our Terms & Conditions and Consent for Telemedicine for details.

Overview

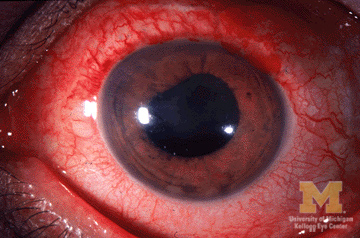

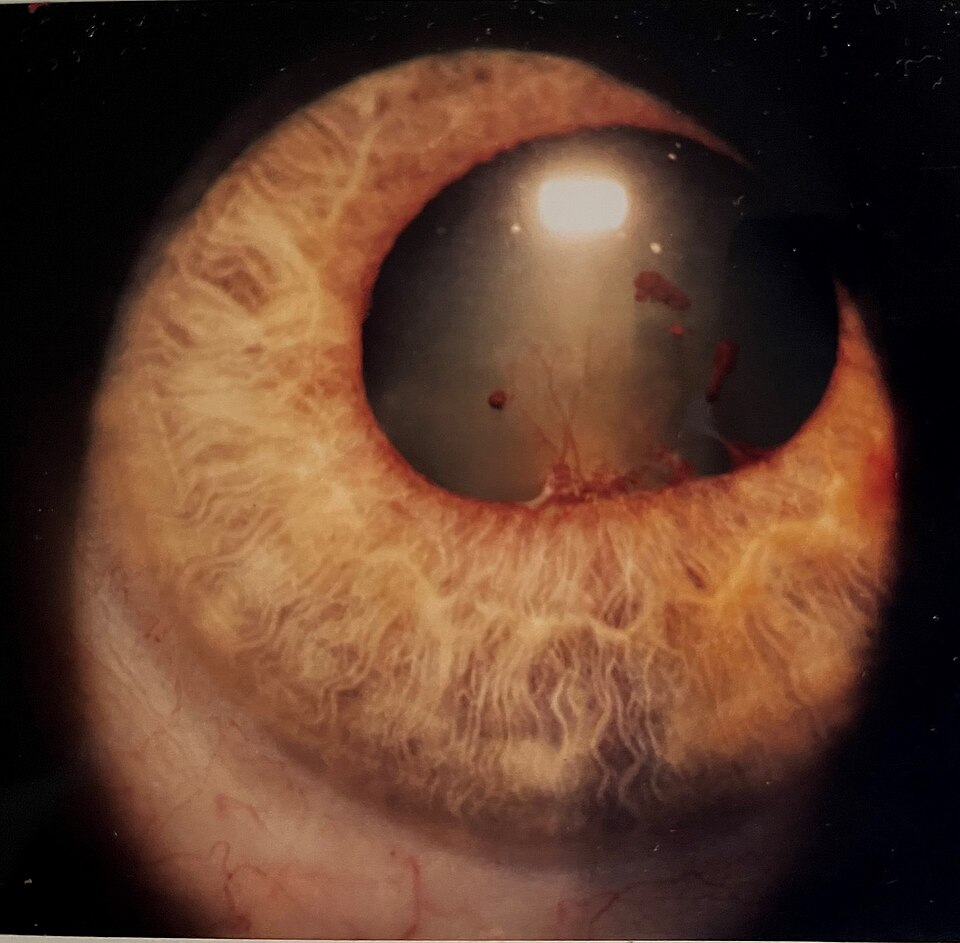

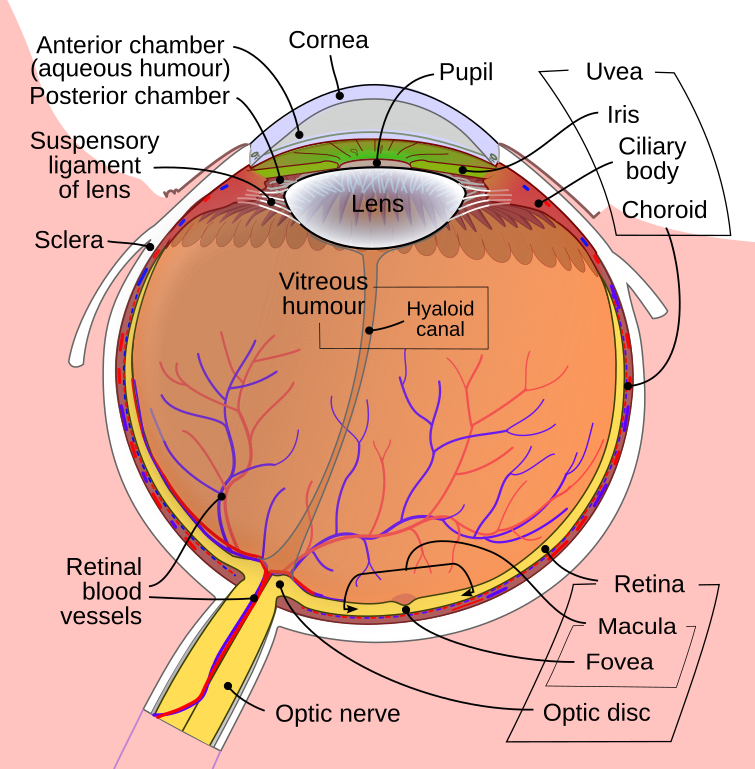

Uveitis is an umbrella term for sight‑threatening inflammation inside the eye. The uvea is the eye’s vascular middle layer (iris, ciliary body and choroid); however, inflammation often spills over to the lens, retina and optic nerve. Doctors classify disease by location—anterior, intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis—and by onset (acute, recurrent or chronic). Worldwide, uveitis causes up to 10 % of legal blindness, yet early treatment can preserve vision.1 In about half of cases the trigger is autoimmune and idiopathic; infections, trauma and systemic diseases explain the rest.2 Symptoms can flare rapidly, so prompt evaluation is essential.

Symptoms

- Eye pain and redness—often severe in anterior attacks

- Photophobia (light sensitivity) and tearing

- Blurred or hazy vision; sudden floaters in intermediate or posterior disease

- Flashes of light or dark curtain if inflammation triggers retinal tear

- Small or irregular pupil from posterior synechiae

Symptoms may appear in one or both eyes and range from mild annoyance to rapid vision loss. Acute anterior uveitis (iritis) is the most common type and tends to strike adults 20‑60 years old.3 Recurrent attacks can lead to cataract, glaucoma and macular edema if left unchecked.4

Causes and Risk Factors

Non‑infectious (immune‑mediated)

- HLA‑B27 spondyloarthropathies (ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic or reactive arthritis)

- Sarcoidosis, Behçet disease, juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- Multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease

Infectious

- Herpes simplex/zoster, cytomegalovirus

- Tuberculosis, syphilis, Lyme disease

- Toxoplasmosis—the leading cause of posterior uveitis in many regions

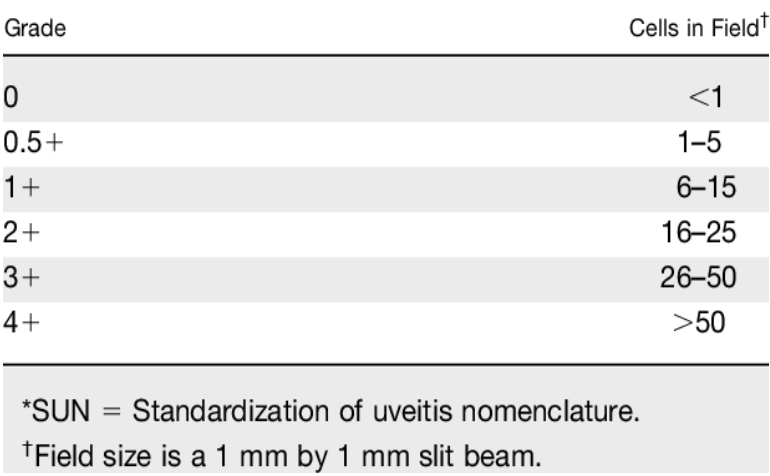

Other risks include ocular trauma, recent intraocular surgery, smoking and age 20‑60 years.1 Machine‑learning analyses from the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group now recognise 25 distinct sub‑types—helping tailor investigation and therapy.5

Vision‑Threat Risk Score (Uveitis)

Enter your details in the following fields to calculate your risk

Risk Level

Recommendation

Diagnosis

Evaluation begins with a dilated slit‑lamp and indirect ophthalmoscopy. Your specialist looks for cells and flare in anterior chamber, vitreous haze, keratic precipitates, choroidal lesions and macular edema. Adjunct tests include:

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) to quantify macular edema

- Fluorescein/indocyanine angiography for vasculitis or choroiditis

- B‑scan ultrasound when media are opaque

- Targeted labs (HLA‑B27, ACE, syphilis serology, TB‑IGRA) and chest imaging when systemic disease suspected

Comprehensive work‑up helps rule out masquerades (lymphoma, endophthalmitis) and guides therapy.4 Retina specialists apply SUN grading to document inflammation and monitor response.6

Treatment and Management

The goal is rapid inflammation control while minimising side‑effects:

- Topical corticosteroids (prednisolone acetate 1 %) and cycloplegic drops for anterior attacks

- Periocular/intravitreal steroids or systemic prednisone for intermediate, posterior and panuveitis

- Steroid‑sparing immunomodulators—methotrexate, mycophenolate, azathioprine—when disease is chronic or bilateral

- Biologic agents: adalimumab received FDA approval in 2016 for non‑infectious intermediate, posterior and panuveitis; biosimilars such as amjevita and idacio followed.7

- Antimicrobials (e.g., anti‑TB therapy, oral acyclovir, trimethoprim‑sulfamethoxazole) for proven infectious causes

- Sustained‑release implants (fluocinolone 0.18 mg, dexamethasone 0.7 mg) provide months of local control but may accelerate cataract and glaucoma.

Close follow‑up is vital to taper steroids safely, detect relapse and manage complications.8

Living with Uveitis and Prevention

Because uveitis can smolder for years, think of care as a marathon, not a sprint:

- Keep all follow‑up visits—flare‑ups can be silent until damage is advanced.

- Take medications exactly as prescribed; never stop steroids abruptly.

- Control systemic diseases with help from rheumatology, infectious‑disease or pulmonology.

- Quit smoking and limit alcohol—both worsen ocular inflammation.

- Use protective eyewear to prevent traumatic uveitis and vaccinate (e.g., shingles) where appropriate.

- Call your eye doctor immediately for new pain, redness or vision change.

With vigilant self‑care and modern therapies, most people maintain useful vision.4 2

Latest Research & Developments

- Biologics & JAK inhibitors: Ongoing phase 2 trials are evaluating upadacitinib and other oral Janus‑kinase blockers for refractory non‑infectious uveitis.

- Long‑acting implants: The 36‑month MERIT study showed fluocinolone 0.18 mg inserts reduced relapse rates by 60 % compared with historical controls.8

- SUN Working Group AI models: Machine‑learning algorithms now assist clinicians in classifying 25 subtypes with >90 % accuracy, streamlining trial enrolment.5

- Biosimilar access: 2024 FDA guidance expanded interchangeability for adalimumab biosimilars, potentially lowering treatment cost.7

Recently Published in Peer-Reviewed Journals

The British journal of ophthalmology

July 23, 2025

Performance of DeepSeek-R1 in ophthalmology: an evaluation of clinical decision-making and cost-effectiveness.

Mikhail D, Farah A, Milad J, et al.

BMC ophthalmology

July 23, 2025

Pediatric peripapillary choroidal neovascularization secondary to ocular sarcoidosis: a long-term follow-up case.

Zong Y, Wang K, Zhang T, et al.

The British journal of ophthalmology

July 22, 2025

Prevalence and incidence of juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis and medication trends in the TriNetX database.

Marshall R, Thorne J, Berkenstock MK

Next Steps

If you suspect uveitis—or your current regimen is no longer controlling flares—schedule an appointment with a fellowship‑trained uveitis specialist. They can:

- Confirm the type of uveitis through targeted imaging and lab work

- Create a personalised treatment plan, including systemic therapy when needed

- Coordinate care with rheumatology, dermatology or infectious‑disease colleagues

You may self‑refer, ask your optometrist or primary‑care provider, or use professional society directories. Kerbside can also connect you directly to the right specialist and streamline scheduling. Bring a timeline of symptoms, medication list and past test results to maximise your visit.9 10