Posterior Capsular Opacification

Also known as Secondary Cataract

Medical Disclaimer: Information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

See our Terms and Telemedicine Consent for details.

Overview

Posterior capsular opacification (PCO) is the most common long-term complication of cataract surgery. Months to years after an otherwise successful lens extraction, residual lens epithelial cells migrate and thicken the thin, clear capsule that holds the intra-ocular lens (IOL). The once-transparent membrane turns hazy or wrinkled, scattering light and causing vision to seem as though the cataract has “grown back.”1 Roughly 20 – 40 % of adults develop some degree of PCO within five years, although modern IOL designs and surgical techniques have lowered that risk.2 Fortunately, a fast outpatient laser procedure—Nd:YAG posterior capsulotomy—can restore clear vision in minutes.

Symptoms

PCO typically creeps up gradually. Common complaints include:

- Blurry, hazy or foggy central vision reminiscent of the original cataract.4

- Increased glare and halos around headlights or bright lights—especially at night.1

- Loss of contrast sensitivity—colors look dull or washed out.

- Difficulty reading fine print or needing more light to read.

- Rarely, double vision in one eye if the opacification is irregular.

Pain, redness or sudden visual blackout are not normal for PCO and should prompt urgent evaluation for other causes.

Causes and Risk Factors

PCO is driven by residual lens epithelial cells that proliferate and migrate across the posterior capsule. Factors that promote this process include:

- Younger age (<65)—a more active healing response raises PCO risk.5

- Pre-existing eye inflammation (uveitis) or diabetes.

- Certain IOL materials and edge designs, although modern square-edge hydrophobic acrylic lenses are protective.9

- Small capsulorhexis (overlapping capsule edge) that shelters migrating cells.

- Systemic or topical corticosteroid use, which can influence cellular behavior.

Even in high-risk eyes, meticulous surgical technique and IOL choice can delay or minimize opacification.

Posterior Capsular Opacification Risk Score

Select your details to estimate risk factors.

Diagnosis

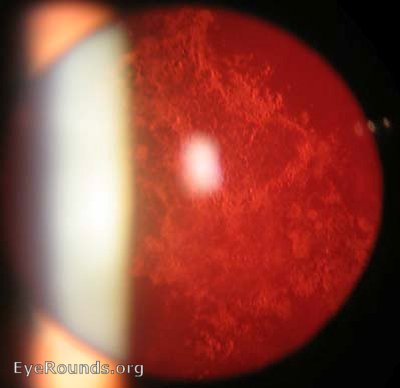

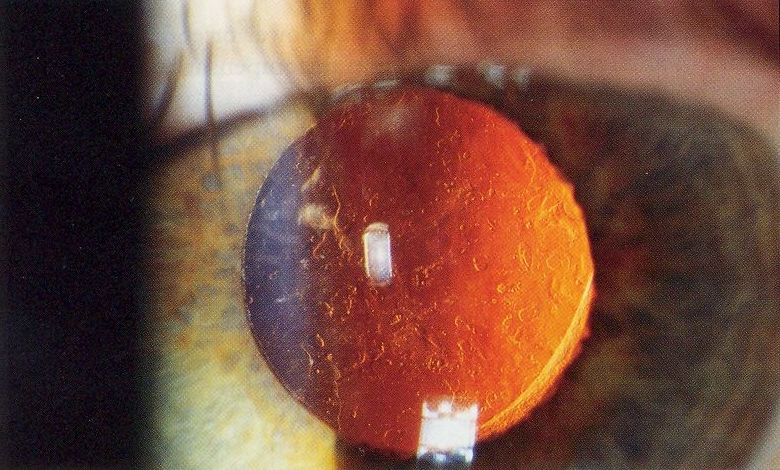

An ophthalmologist confirms PCO with a slit-lamp examination:

- Diffuse illumination shows a gray-white film or pearly cell clusters (“Elschnig pearls”) behind the IOL.3

- Retro-illumination highlights capsular folds and pearl-like opacities crossing the visual axis.5

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT) may be used to document membrane thickness before and after laser treatment.

- Visual-acuity & contrast-sensitivity tests quantify functional impact.

No blood tests are required; imaging is painless and completed in-office.

Treatment and Management

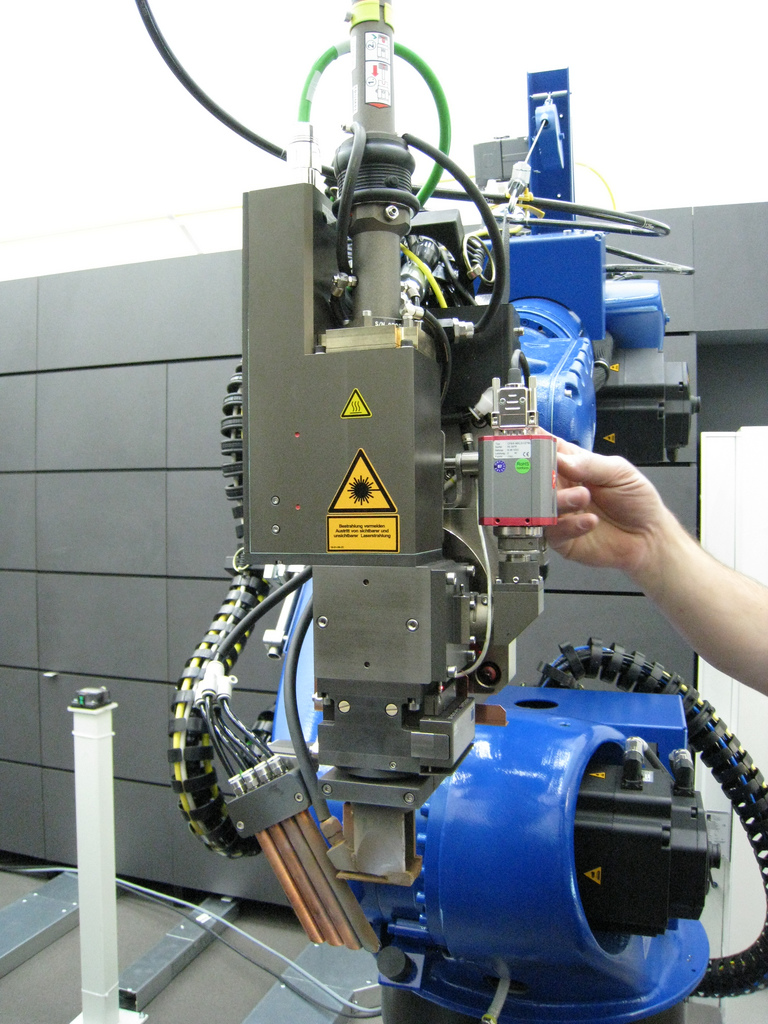

If PCO degrades best-corrected visual acuity or causes symptomatic glare, the gold-standard treatment is an Nd:YAG posterior capsulotomy. During this five-minute procedure, a focused laser creates a central opening in the cloudy capsule, instantly clearing the visual axis.3 Key points:

- Outpatient convenience—no needles; topical anesthesia and dilating drops suffice.6

- Vision recovery is rapid—many notice improvement within hours once dilation clears.

- Risks are low but include transient eye-pressure spikes, floaters, cystoid macular edema or, rarely, retinal detachment. Most receive a short course of anti-inflammatory drops.

- One-time solution—the opening does not re-opacify, though the other eye can develop PCO independently.

Patients with mild haze or minimal symptoms may defer laser until activities of daily living are affected.

Living with Posterior Capsular Opacification and Prevention

Can PCO be prevented entirely? Not yet—but several strategies lower the odds:

- Choose modern square-edge IOLs when planning cataract surgery—these designs mechanically block migrating cells.2

- Maintain good control of diabetes and inflammation; unstable blood sugar and uveitis accelerate capsule scarring.1

- Attend routine post-operative visits so subtle haze is caught before vision plunges.

- Protect eyes from UV light with quality sunglasses—UV exposure may influence lens-cell behavior.

After capsulotomy, most people resume normal activities the same day, although driving is discouraged until dilation wears off. Reading glasses or an updated spectacle prescription may be needed once vision stabilizes.

Latest Research & Developments

Innovation aims to stop PCO before it starts:

- Enhanced-depth OCT & AI algorithms can grade capsule clarity objectively and predict who will need laser, reducing unnecessary follow-ups.7

- IOL surface modifications (heparin, phosphoryl-choline or micro-texturing) show promise in laboratory studies for inhibiting lens-cell adhesion.

- Drug-eluting capsular rings delivering anti-proliferative agents are in early clinical trials.

- A large post-mortem eye-bank study documented a marked decline in capsulotomy rates over the past decade, underscoring the impact of modern surgery.8

Recent Peer-Reviewed Research

LIRTS Viewer: A Web-Based Resource to View the Transcriptional Response of Lens Epithelial Cells to Injury.

Gorai S, Faranda AP, Shihan MH, et al.

Aravind Pseudoexfoliation Study (APEX): 10-Year Postoperative Results.

Haripriya A, Chandrashekharan S, Schehlein EM, et al.

PERK Regulates Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Through Autophagy and Lipid Metabolism in Lens Epithelial Cells.

Wang X, Chen B, Chen J, et al.

Next Steps

If you notice hazy vision months or years after cataract surgery, book an appointment with a cataract or anterior-segment specialist. They can confirm PCO, check eye pressure, and perform a same-day laser capsulotomy when appropriate.1 Most general ophthalmologists also offer this service, but complex cases (dense fibrosis, single-eye patients, high myopes) benefit from subspecialty expertise.3

How to schedule: Your regular eye-care provider can refer you, yet many laser suites accept self-referrals. If wait-lists are long, you can connect directly to a fellowship-trained surgeon through Kerbside for timely second opinions, imaging review and coordinated capsulotomy appointments.

Trusted Specialists

Board-certified providers specializing in Posterior Capsular Opacification.