Diplopia

also known as Double Vision

Last updated August 5, 2025

Medical information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

See our Terms & Conditions and Consent for Telemedicine for details.

Overview

Diplopia is the medical term for seeing two images of a single object. It can be binocular (present only when both eyes are open and usually due to misalignment) or monocular (persists in one eye and is often optical). Sudden or persistent double vision may signal serious neurologic or systemic disease, but many cases are temporary or related to fatigue, medications, or refractive error.1 Prompt evaluation is important because timely treatment of the underlying cause—from dry eye to cranial-nerve palsy—can restore single vision and prevent accidents, anxiety, and loss of independence.2

Symptoms

People describe diplopia in many ways, but typical features include:

- Two separate, overlapping, or shadowed images that may be side-by-side (horizontal), one above the other (vertical), or diagonal.

- Eye strain, headache, or nausea when the brain struggles to fuse the images.4

- Closing or covering one eye improves binocular diplopia but not monocular diplopia.

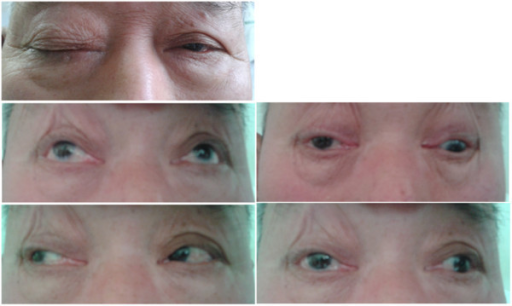

- Associated signs such as droopy eyelid, eye turn, dizziness, or difficulty focusing at certain distances.

Because diplopia can fluctuate with fatigue or gaze position, keeping a symptom diary (which eye, what direction, time of day) helps clinicians pinpoint the cause.

Causes and Risk Factors

Anything that alters the smooth coordination of the eyes can create double vision. Common categories include:

- Ocular surface and refractive problems such as dry eye, cataract, or astigmatism that split light entering a single eye.5

- Eye-muscle imbalance from strabismus in childhood or age-related “sagging eye syndrome,” where stretched connective tissue lets the eyes drift slightly off target.6

- Cranial-nerve palsies (III, IV, VI) caused by diabetes, hypertension, stroke, aneurysm, or trauma.

- Systemic & neurologic conditions: myasthenia gravis, thyroid eye disease, multiple sclerosis, migraine, brain tumors, or elevated intracranial pressure.

- Medication effects (anticonvulsants, antihypertensives) and toxic exposures (alcohol, solvents).

Diplopia Recurrence Risk Score

Enter your details in the following fields to calculate your risk

Risk Level

Recommendation

Diagnosis

Evaluation begins with distinguishing monocular from binocular diplopia and looking for red-flag causes:

- History & exam: cover–uncover, alternate-cover, and Maddox rod tests measure the deviation; pupils, eyelids, and ocular motility are assessed for nerve palsy.7

- Slit-lamp and refraction rule out corneal irregularities or lens problems.8

- Neuro-imaging (MRI or CT) is ordered for acute binocular diplopia with neurologic signs, suspected aneurysm, or orbital mass.

- Targeted lab tests include blood glucose, thyroid antibodies, acetylcholine-receptor antibodies (myasthenia), and inflammatory markers.

Children or adults with longstanding misalignment may need specialized sensory tests (Worth 4-dot, Bagolini lenses) to measure suppression or fusion reserves.

Treatment and Management

The remedy depends on the underlying cause, but options often include:

- Corrective lenses or prisms to realign images or neutralize monocular optical distortions.9

- Patching or opaque contact lenses for temporary relief when prisms are not feasible.

- Botulinum-toxin injections into overactive extra-ocular muscles to reduce deviations in selected cranial-nerve palsies.

- Surgery (muscle recession, resection, or adjustable sutures) for stable strabismus or trauma-related deviations.

- Treating systemic disease—for example, steroids for myasthenia gravis crisis, antithyroid therapy for Graves ophthalmopathy, or strict glycemic control for diabetic palsy.10

Most ischemic cranial-nerve palsies resolve within 3–6 months; prisms or patching can bridge that period.

Living with Diplopia and Prevention

Adapting daily routines can lessen symptoms and lower recurrence risk:

- Manage vascular risks—maintain blood pressure <130/80 mmHg, keep HbA1c <7 %, and exercise regularly.11

- Follow the 20-20-20 rule during screen work and use proper lighting to reduce eye strain.12

- Protect your eyes and head with safety glasses and helmets during sports or hazardous activities.

- Limit alcohol and stop smoking, both of which impair micro-vascular circulation.

- Keep corrective-lens prescriptions current and schedule comprehensive eye exams every 1–2 years, or sooner if symptoms change.

Many patients learn compensatory head positions or use stick-on Fresnel prisms while awaiting definitive therapy.

Latest Research & Developments

Exciting advances are reshaping care:

- Age-related "sagging eye syndrome" is now recognized as a leading cause of new-onset diplopia in adults >60, guiding less invasive surgical corrections.13

- Virtual-reality–based fusion therapy is under NEI-funded study for convergence insufficiency and residual strabismic diplopia.14

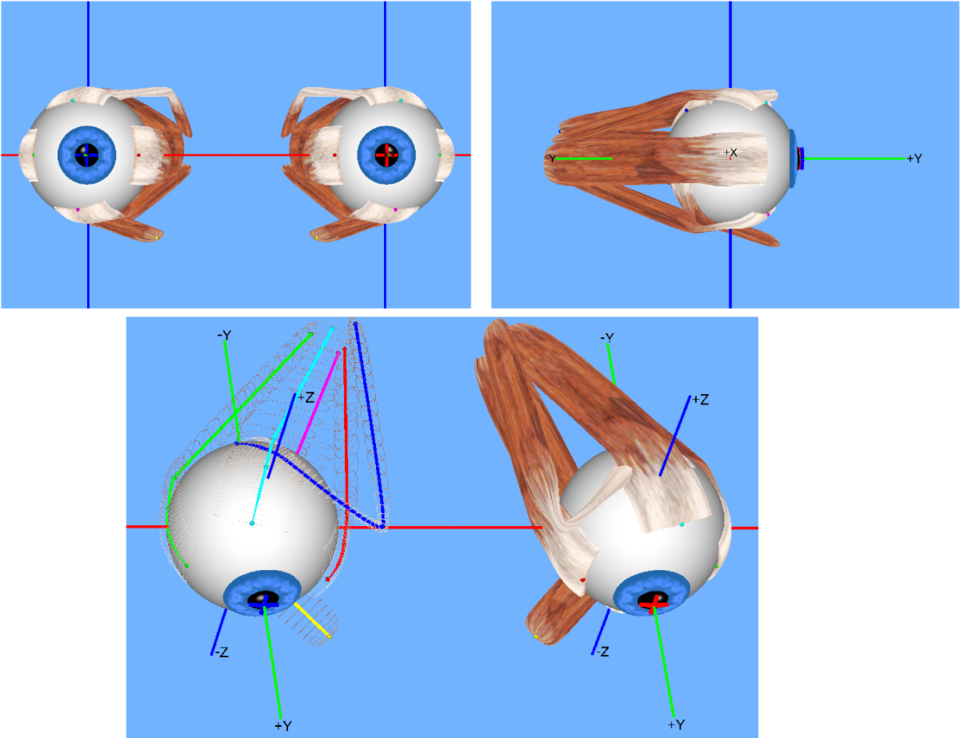

- High-resolution ocular-motor MRI allows 3-D mapping of extra-ocular muscle pulleys, refining surgical planning.

- Extended-release botulinum formulations aim to double treatment intervals for neurologic palsies.

- Wearable eye-tracking glasses are being tested to monitor real-world misalignment and trigger early intervention.

Recently Published in Peer-Reviewed Journals

Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society

July 22, 2025

Causes of Diplopia, Strabismus Patterns, and Ocular Motor Features in Patients With Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 27B.

Gold DR, Bery AK, Moukheiber E, et al.

BMC ophthalmology

July 14, 2025

Correlations between the clinical characteristics of diabetic trochlear nerve palsy and diplopia severity.

Xue Z, Cao T, Li X, et al.

JAMA ophthalmology

June 26, 2025

Intermittent Diplopia Following Resolution of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma.

Siranart N, Anukoolwittaya P

Next Steps

Persistent or sudden diplopia—especially when accompanied by headache, droopy eyelid, or neurologic symptoms—should be evaluated by a neuro-ophthalmologist or strabismus specialist. These providers integrate eye-movement testing with brain and systemic work-ups.15 If subspecialty care is scarce locally, an ophthalmologist can initiate urgent imaging and refer on.

How to schedule: Primary eye-care doctors or emergency departments can expedite referrals for dangerous causes. Many tertiary centers accept self-referrals, and Kerbside can connect you directly with board-certified subspecialists for second opinions, prism prescriptions, or surgery planning without long waits.16