Ptosis

Also known as Droopy Eyelid

Medical Disclaimer: Information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

See our Terms and Telemedicine Consent for details.

Overview

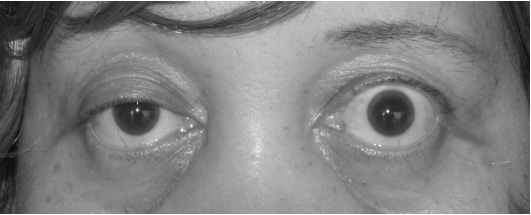

Ptosis (pronounced TOE-sis) is the medical term for a drooping upper eyelid. It can be congenital (present at birth) or acquired later in life and may affect one eye (unilateral) or both eyes (bilateral). The problem occurs when the levator palpebrae superioris muscle or its nerve supply cannot keep the lid fully open, allowing the lid edge to sag over the pupil and sometimes block vision.1 In babies, untreated severe ptosis can cause amblyopia (“lazy eye”), while in adults the condition may interfere with driving, reading, or interpersonal interaction. Because ptosis can occasionally signal serious neurologic disease, prompt evaluation is important.2

Symptoms

- Visible droop: The upper eyelid margin rests lower than usual; people may notice asymmetry in photos or mirrors.1

- Blocked or blurred vision: The lid may obscure the upper visual field; children often tip the head back or raise eyebrows to compensate.3

- Eye strain and fatigue: Forehead muscles over-work to hold lids up, leading to ache or headache by day’s end.

- Excess tearing or dryness: Malpositioned lids disrupt the tear film.

- Intermittent double vision or fluctuating droop: Can occur in myasthenia gravis or oculomotor nerve palsy.

Causes and Risk Factors

Clinicians group ptosis by underlying mechanism:

- Aponeurotic (involutional) – stretching or dehiscence of the levator tendon with aging, long-term contact-lens wear, or after cataract/laser surgery.1

- Myogenic – congenital levator dysgenesis, chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia, or myasthenia gravis.

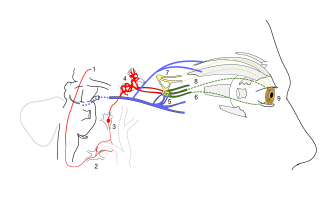

- Neurogenic – third-nerve palsy, Horner syndrome, or Marcus Gunn jaw-wink synkinesis.

- Mechanical – lid tumours, chalazia, dermatochalasis, or scarring that weigh the lid down.

- Traumatic – laceration or orbital fracture affecting the levator.

Major risk factors include older age, prior ocular surgery, diabetes or stroke, neuromuscular disorders, and a family history of congenital ptosis.3

Adult Acquired Ptosis Risk Estimator

Select your details to estimate risk factors.

Diagnosis

Evaluation begins with a dilated eye examination to rule out sight-threatening disease. Key elements are:

- Margin–Reflex Distance 1 (MRD-1): millimetres from corneal light reflex to upper-lid margin quantify severity.

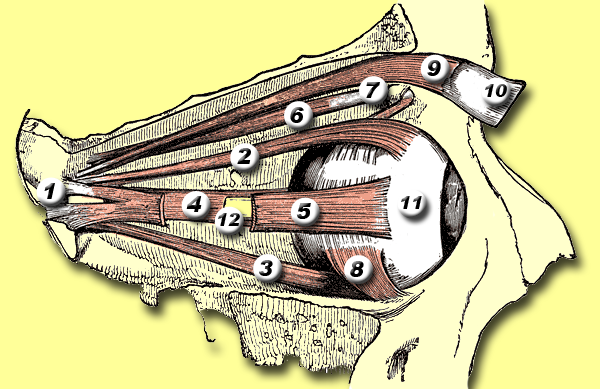

- Levator function test: measures excursion of the lid with frontalis muscle neutralised.

- Pupils and eye movements: deficits suggest neurogenic causes.

- Fatigue testing or ice pack test: screens for myasthenia gravis when droop fluctuates.1

- Visual-field perimetry: documents superior-field loss for insurance approval of surgery.3

- Imaging: MRI or CT if a mass, Horner syndrome, or cranial-nerve palsy is suspected.

Treatment and Management

Non-surgical approaches

- Oxymetazoline 0.1 % (Upneeq) eyedrops: FDA-approved in 2020, this α-adrenergic agonist stimulates Müller’s muscle and can raise the lid 1–2 mm for several hours – useful in mild acquired ptosis or for surgical ineligible patients.5

- Ptosis crutch glasses for temporary palliation.

Surgical options (usually outpatient with local anaesthetic)

- Levator advancement or resection: first-line for good levator function (> 10 mm).

- Müller muscle–conjunctival resection: chosen when a phenylephrine test shows lid elevation.

- Frontalis sling: autogenous fascia lata or silicone rod suspends the lid to brow in congenital or poor-function cases.

- Adjunct blepharoplasty: removes excess skin and fat when dermatochalasis coexists.4

Living with Ptosis and Prevention

Most people live normal lives with ptosis, but these steps can minimise complications:

- Regular eye checks: Children need yearly exams to prevent amblyopia; adults should return if vision changes or droop worsens.2

- Manage systemic conditions: Good diabetes and blood-pressure control lower the risk of nerve palsies.

- Protect the cornea: Use lubricating drops or ointment if incomplete lid closure causes dryness.

- Post-surgery care: Follow wound-care instructions and attend follow-ups; temporary swelling or under-correction is common early on.1

- Medication review: Report any new droop after starting topical β-blockers, botulinum toxin, or systemic drugs affecting neuromuscular junction.

Latest Research & Developments

- Pharmacologic lift: Continued post-marketing studies of oxymetazoline 0.1 % show sustained eyelid elevation with minimal systemic absorption.5

- Gene-editing in congenital ptosis: Early-phase work is exploring CRISPR-based correction of FOXL2 mutations implicated in Blepharophimosis-Ptosis-Epicanthus Inversus Syndrome.

- 3-D-printed custom frontalis slings aim to improve cosmesis and reduce revision rates.

- Intraoperative digital pupillometry is being tested to fine-tune levator resection amounts in real time, reducing asymmetry.

Recent Peer-Reviewed Research

Orbital apex syndrome and ophthalmic artery occlusion caused by acute sinusitis.

Liao D, Yang X, Li R

Refractive status and ocular biometric parameters in children undergoing the levator muscle-conjoint fascial sheath complex suspension.

Fu T, Ma S, Ai H, et al.

Original research: factors related to persistent amblyopia after surgical correction in unilateral congenital blepharoptosis.

Chen YH, Huang PW, Tsai YJ

Next Steps

Who to see: The ideal provider is an oculoplastic (eyelid) specialist – an ophthalmologist with fellowship training in plastic and reconstructive surgery of the eyelids and orbit.

How to schedule: Ask your optometrist, paediatrician, or primary-care doctor for a referral, or self-refer to practices that list “oculoplastic or ophthalmic plastic surgery” services. Non-urgent appointments may book weeks ahead, but sudden droop with double vision, unequal pupils, or headache warrants same-day emergency evaluation.1

Need a second opinion? Kerbside can connect you directly with vetted eyelid specialists for virtual or in-person consultations, expediting care when every millimetre of lid height matters.