Posterior Vitreous Detachment

also known as PVD

Last updated July 31, 2025

Medical information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

See our Terms & Conditions and Consent for Telemedicine for details.

Overview

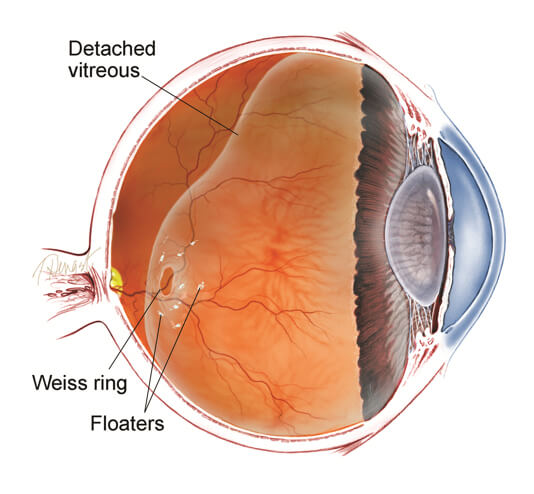

Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) happens when the aging gel (vitreous) that normally fills the eye liquefies and peels away from the light‑sensing retina. It is remarkably common—about two‑thirds of people older than 70 show signs of a PVD—and for most it is a harmless milestone of ocular aging.1 The separation typically completes over several weeks to months, during which patients notice new floaters or flashes but retain good central vision. The main danger is that traction from the shrinking gel can rip the fragile retina, leading to retinal tears or, less commonly, a sight‑threatening retinal detachment.2 Early recognition and follow‑up ensure tears are sealed before fluid tracks underneath the retina.

Symptoms

Most people experience one or more of the following:

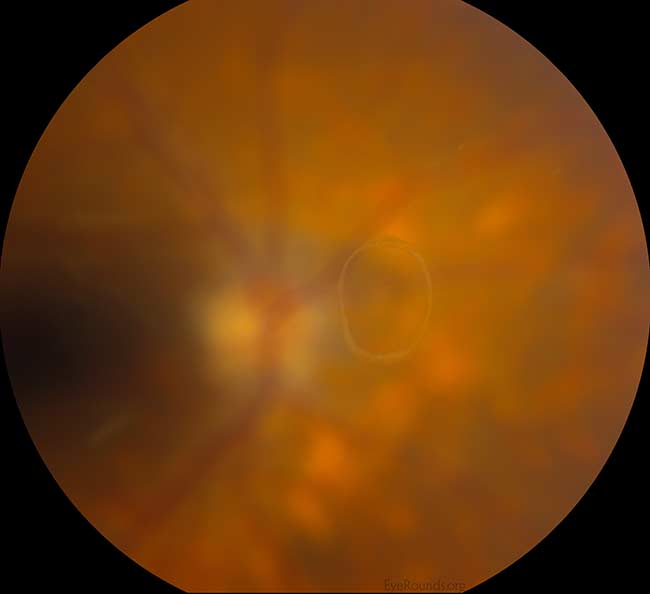

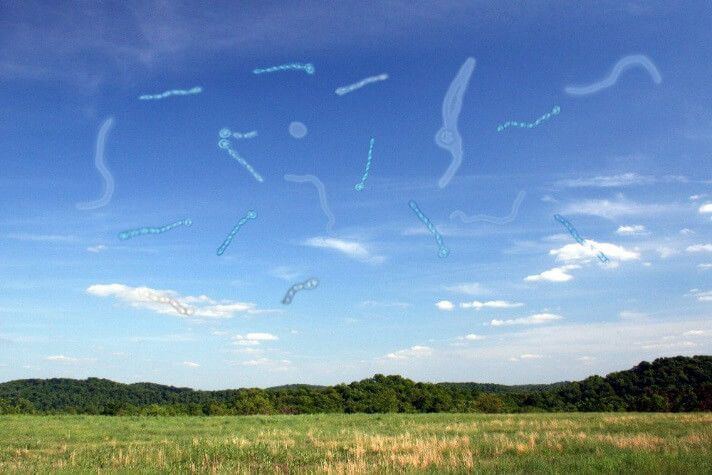

- Floaters: dark specks, cobwebs, or a ring‑shaped Weiss ring that drift with eye movement.4

- Flashes (photopsias): brief arcs of light in the side vision caused by vitreous tugging on the retina.2

- Heavy shower of floaters, veil, or curtain: may signal a retinal tear or detachment and requires same‑day examination.

- Usually no pain or redness.

Although floaters gradually fade from awareness, any sudden increase in floaters, flashes, or a shadow in vision should trigger an urgent dilated eye exam.

Causes and Risk Factors

PVD occurs when enough microscopic collagen fibers between the vitreous and retina break. Contributing factors include:

- Age > 50 years—risk rises steeply each decade.3

- Nearsightedness (myopia)—especially > −6 diopters.

- Prior eye surgery (e.g., cataract, YAG capsulotomy).

- Ocular trauma or inflammation.

- Systemic conditions such as diabetes or connective‑tissue disorders.

Because the vitreous in one eye usually mirrors the other, a PVD in one eye predicts a similar event in the fellow eye within 6–24 months.9

Posterior Vitreous Detachment Risk Calculator

Enter your details in the following fields to calculate your risk

Risk Level

Recommendation

Diagnosis

A comprehensive, dilated eye examination remains the gold standard:

- Indirect ophthalmoscopy & scleral depression to inspect the far retinal periphery for tears.

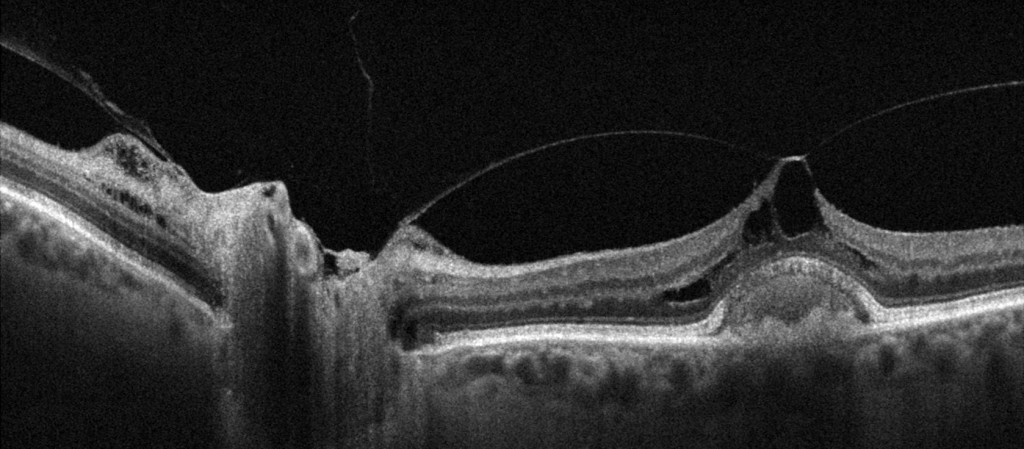

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) can demonstrate a lifted posterior hyaloid face or rule out subtle macular holes.2

- B‑scan ultrasound is invaluable when media are opaque (dense floaters, hemorrhage).

- Follow‑up exams at 4–6 weeks and again at 3 months catch delayed tears that develop after an apparently benign initial presentation.1

Treatment and Management

No treatment is required for an uncomplicated PVD. Management focuses on preventing and treating complications:

- Retinal tears are sealed with in‑office laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy, reducing the risk of retinal detachment from >30 % to <8 %.3

- Retinal detachment is a surgical emergency treated with vitrectomy, scleral buckle, and/or pneumatic retinopexy.5

- Persistent, vision‑limiting floaters—rarely—may be removed with pars plana vitrectomy or treated with floater‑specific YAG vitreolysis after careful counseling.

Living with Posterior Vitreous Detachment and Prevention

Most patients adjust well once they understand that floaters usually fade and flashes subside after the vitreous fully detaches:

- Monitor symptoms: seek immediate care for new flashes, many new floaters, a “curtain,” or vision drop.4

- Routine eye exams: yearly dilated exams after age 60 or sooner if myopic, diabetic, or post‑surgery.

- Protect the eyes: use safety eyewear during sports or yardwork to prevent trauma‑induced retinal tears.

- Control systemic disease: good diabetes and blood‑pressure management support retinal health.9

Simple lifestyle adaptations—such as moving the eyes gently instead of rapidly scanning—can temporarily move floaters away from the line of sight.

Latest Research & Developments

Current studies aim to predict and prevent vision‑threatening sequelae of PVD:

- Large database analyses show about 7.4 % of eyes develop delayed retinal tears within six years, with half occurring in the first five months.6

- Machine‑learning algorithms applied to OCT are being trained to flag high‑risk vitreoretinal traction patterns before a tear occurs.

- Prospective trials are evaluating prophylactic 360‑degree laser in very high‑risk fellow eyes.

- Pharmacologic vitreolysis (enzymatic agents that liquefy the vitreous) is under investigation to shorten symptomatic periods.

- Case reports suggest spontaneous macular hole closure after PVD, highlighting the complex biomechanics of the posterior hyaloid.8

Recently Published in Peer-Reviewed Journals

Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.)

July 7, 2025

Clinical Outcomes of Scleral Buckling in Elderly Patients with Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment: A Retrospective Cohort Study.

Zhu X, Xu M, Chen N, et al.

Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.)

June 23, 2025

EVALUATION OF FELLOW EYES IN IDIOPATHIC MACULAR HOLE CASES WITH OPTICAL COHERENCE TOMOGRAPHY ANGIOGRAPHY.

Ulusoy MO, Sarıyeva-İsmayilov A, Can RB

Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.)

June 19, 2025

Optic disc pit maculopathy-like retinoschisis without a clinically visible optic disc pit.

Kim YJ, Ribarich N, Querques G, et al.

Next Steps – See a Retina Specialist

Who to see: If you notice new flashes, a burst of floaters, or any shadow, request an urgent appointment with a board‑certified retina specialist—these surgeons have the tools to detect and seal tears the same day.3

How to schedule: Tell the scheduler you have “possible retinal tear after new floaters and flashes.” Many offices reserve same‑day slots for these calls. If no specialist is immediately available, go to the emergency department—retinal detachments progress quickly.5

You can also connect directly to the right retina specialist on Kerbside for rapid triage and second opinions.

Trusted Providers for Posterior Vitreous Detachment

Dr. Emily Eton

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Harvard Medical School

Dr. Grayson Armstrong

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Ophthalmology

Dr. Jose Davila

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Retina/Vitreous Surgery

Dr. Nicholas Carducci

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine