Macular Hole

also known as Full‑Thickness Macular Hole

Last updated July 29, 2025

Medical information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

See our Terms & Conditions and Consent for Telemedicine for details.

Overview

A macular hole is a full‑thickness break in the very center of the retina—the fovea—where the sharpest vision is formed. Although small (often < 0.4 mm wide), the defect disrupts the finely layered photoreceptors that enable reading, driving, and facial recognition. Most holes develop idiopathically as the gel‑like vitreous shrinks with age and tugs on the thin foveal tissue. Less commonly, trauma, high myopia, or prior retinal surgery trigger a hole. While macular holes account for only 1 in 10 000 new ophthalmology visits each year, they cause up to 3 % of legal blindness in industrialized countries.1 Timely surgery closes more than 90 % of stage 2–4 holes, restoring two or more lines of vision in half of patients.2

Symptoms

- Blurred or hazy central vision—letters and numbers lose sharp edges.

- Metamorphopsia—straight lines appear kinked or wavy on an Amsler grid.

- Central scotoma—a dark or gray spot obscuring faces or road signs.

- Difficulty with fine tasks such as threading a needle or reading small print.

Symptoms usually progress over weeks as a stage 1 impending hole advances to stage 2–4 full‑thickness defects. Peripheral vision remains normal, so patients may not notice the deficit until the fellow eye is covered. Sudden visual distortion after ocular trauma or cataract surgery should raise suspicion for an acute traumatic macular hole.3 An at‑home Amsler grid helps detect subtle change, but any new central blur warrants prompt dilated examination.4

Causes and Risk Factors

Primary mechanism: tangential and anteroposterior traction from the posterior vitreous as it liquefies and peels away from the retina with age.5 When the hyaloid remains tethered to the fovea, continued traction leads to foveolar cyst, roof dehiscence, and ultimately a full‑thickness hole.6

Major risk factors

- Age > 60 years (incidence peaks in the seventh decade)

- Female sex (≈ 2 : 1 female : male ratio)

- High myopia (axial length > 26 mm)

- Ocular trauma or prior retinal detachment repair

- Epiretinal membrane or vitreomacular traction (VMT)

- Contralateral eye with no posterior vitreous detachment—up to 15 % develop a hole within five years

Systemic factors such as diabetes, inflammatory eye disease, and collagen disorders modestly increase risk by altering vitreous structure or healing capacity.

Macular Hole Progression Risk Estimator

Enter your details in the following fields to calculate your risk

Risk Level

Recommendation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis combines clinical exam and modern imaging:

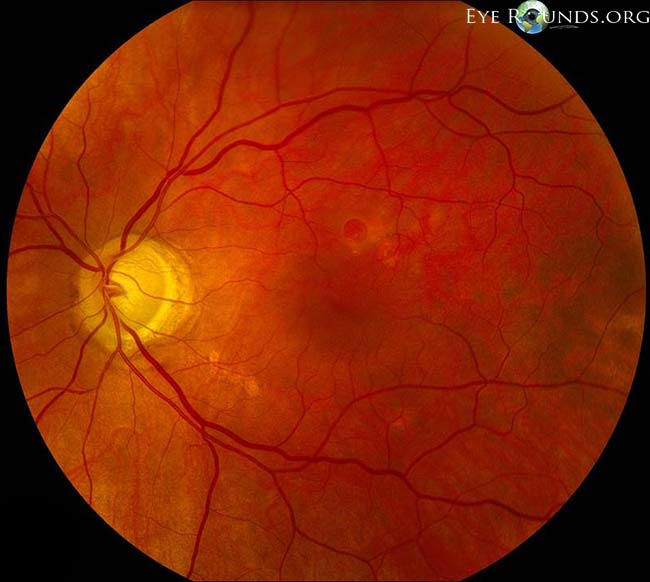

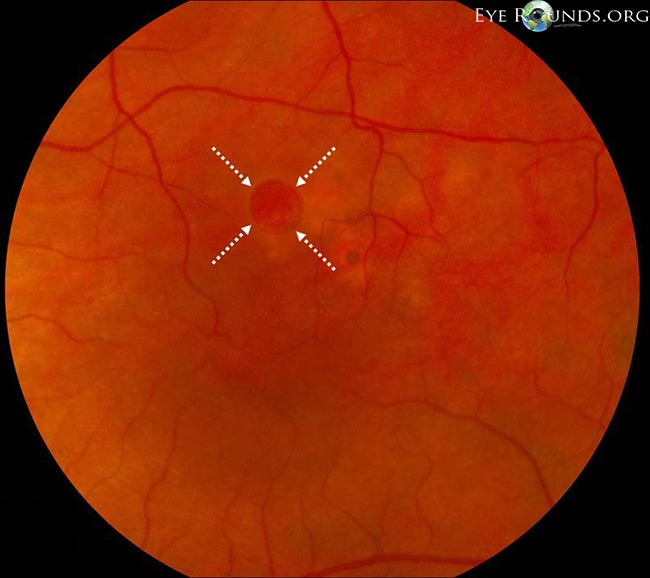

- Dilated biomicroscopy reveals the classic round, reddish foveal defect with a gray cuff of subretinal fluid.

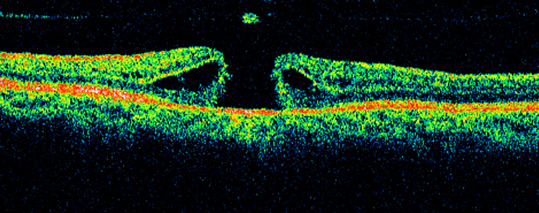

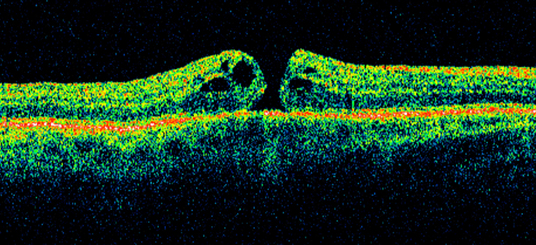

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT) confirms full‑thickness retinal loss from the internal limiting membrane to the retinal pigment epithelium and measures minimal hole diameter—critical for staging and prognostication.7

- Watzke‑Allen slit test or a modified line test helps assess retinal function when OCT is unavailable.

- Ocular coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) can visualize perifoveal capillary remodeling in chronic holes.

Two main classification systems are used. The Gass biomicroscopic stages 1–4 describe clinical evolution, while the International Vitreomacular Traction Study (IVTS) categorizes holes as small (≤ 250 µm), medium (251–400 µm), or large (> 400 µm) on OCT.8

Treatment and Management

Observation is reasonable for stage 1 impending holes; 40 % close spontaneously. Once a full‑thickness defect forms, the standard of care is pars plana vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane (ILM) peel and gas tamponade. Success rates exceed 90 % for medium‑sized holes.9 Traditional protocols required 5–7 days of strict face‑down posturing, but recent randomized trials and Mayo Clinic data show comparable closure rates with limited or no face‑down positioning, greatly improving patient comfort.10

Adjuncts include:

- Ocriplasmin (Jetrea)—a proteolytic enzyme approved for small holes with VMT; 40 % anatomical closure in a pivotal NEJM trial.11

- Autologous ILM or lens‑capsule flap techniques for chronic > 400 µm holes.

- 25‑ or 27‑gauge transconjunctival vitrectomy devices that shorten surgery time and speed recovery.

Potential complications—cataract acceleration, retinal tear, elevated intraocular pressure—are discussed pre‑operatively.

Living with Macular Hole and Prevention

Before surgery, use good lighting, enlarge text on digital devices, and rely on the fellow eye for critical tasks. After vitrectomy:

- Follow head‑position instructions carefully if advised; even 2–3 days of positioning increases closure odds for large holes.

- Avoid air travel or high‑altitude hiking until the intraocular gas dissolves (4–8 weeks) to prevent dangerous eye‑pressure spikes.

- Check an Amsler grid weekly and notify your surgeon if distortion returns.

- Maintain systemic wellness—control blood pressure and blood sugar, stop smoking—to support retinal healing.

Preventive strategies focus on the second eye. A complete posterior vitreous detachment in the fellow eye lowers risk dramatically, so periodic OCT monitoring is warranted until a PVD is documented.12 Protective eyewear can reduce the chance of traumatic holes.

Latest Research & Developments

- Pharmacologic vitreolysis: Phase 3 data continue on next‑generation integrin‑cleaving enzymes aimed at releasing vitreomacular traction with fewer side‑effects than ocriplasmin.

- ILM tissue engineering: Multicenter trials of human amniotic membrane plug and platelet‑rich fibrin scaffold report > 90 % closure in holes > 700 µm.

- Gas alternatives: Controlled studies of filtered air show equivalent closure to 12 % C3F8 for small‑medium holes, eliminating altitude restrictions.

- Face‑down positioning reconsidered: A 2024 AAO Ophthalmic Technology Assessment concluded that limited positioning (≤ 24 h) suffices for most idiopathic holes, influencing global practice guidelines.13

Recently Published in Peer-Reviewed Journals

BMC ophthalmology

July 22, 2025

Artificial intelligence in predicting macular hole surgery outcomes: a focus on optical coherence tomography parameters.

Ozturk Y, Ağın A, Yelmi B, et al.

Ophthalmology. Retina

July 11, 2025

Internal limiting membrane flap and insertion techniques improve prognosis in macular hole-associated retinal detachment.

Zhu K, Lei B, Wang L, et al.

BMC ophthalmology

July 2, 2025

Predicting anatomical success and retinal restoration following macular hole surgery using optical coherence tomography parameters.

Ozal E, Ermis S, Gul C, et al.

Next Steps

If you experience sudden central blur or notice a dark spot on your Amsler grid, arrange an exam with a retina specialist within one week. Delays beyond six months reduce the likelihood of visual recovery. You may self‑refer, request an urgent appointment through your optometrist, or use Kerbside to connect directly to an experienced surgeon.

At your visit, expect pupil dilation, OCT imaging, and a discussion of surgery versus observation. Bring a list of medications, medical history, and any prior eye records. Most vitrectomies are outpatient procedures lasting 30–60 minutes; plan for a driver and allow several days off work for recovery.14 Early action maximizes the chance of sealing the hole and regaining sharp central vision.

Trusted Providers for Macular Hole

Dr. Emily Eton

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Harvard Medical School

Dr. Grayson Armstrong

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Ophthalmology

Dr. Jose Davila

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Retina/Vitreous Surgery

Dr. Nicholas Carducci

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine