Scleritis

Last updated August 4, 2025

Medical information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

See our Terms & Conditions and Consent for Telemedicine for details.

Overview

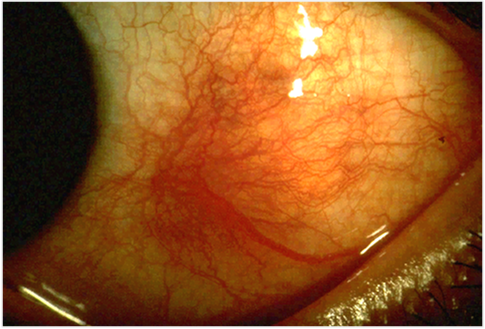

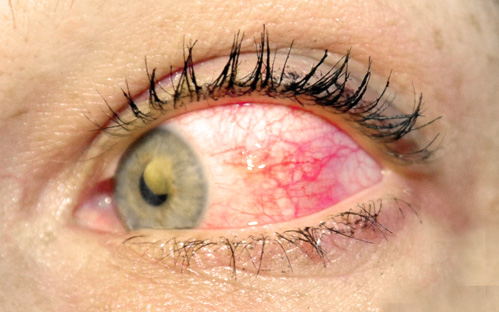

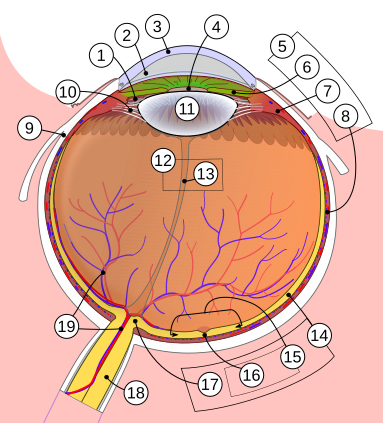

Scleritis is a serious, sight-threatening inflammation of the sclera—the tough, white, outer wall of the eye. Unlike the more superficial episcleritis, scleritis affects the full thickness of the scleral tissue, often producing deep, boring eye pain, violaceous redness, and potential damage to adjacent ocular structures. Up to 50 % of cases are linked to systemic autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or granulomatosis with polyangiitis.1 Prompt diagnosis and immunosuppressive therapy are critical because uncontrolled inflammation can lead to vision-threatening complications including keratitis, glaucoma, and globe perforation.2

Symptoms

- Severe ocular pain that may radiate to the temple, jaw, or brow and can awaken patients at night.

- Diffuse or sectoral redness that often appears violaceous rather than bright red.

- Tearing, photophobia, and blurred vision; visual acuity may drop if the cornea, retina, or optic nerve becomes involved.

- Restricted eye movement pain—looking in certain directions worsens discomfort.

Symptoms usually develop in adults aged 40–60 but can occur at any age.3 Because redness from scleritis will not blanch after phenylephrine drops (unlike conjunctivitis), this bedside test helps differentiate the two.4

Causes and Risk Factors

Roughly half of patients have an underlying systemic disease. The most common associations include rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and relapsing polychondritis.5 Infectious scleritis—bacterial, fungal, viral, or parasitic—accounts for about 5 % of cases, often following trauma or surgery. Additional risk factors are:

- Female sex (autoimmune forms predominate in women).6

- Age 40–60 years.

- History of ocular surgery, especially pterygium excision with adjunctive mitomycin C.

- Systemic vasculitides and connective-tissue disorders.

Necrotizing scleritis is strongly linked to long-standing autoimmune disease and carries the highest risk of perforation.7

Scleritis Relative Risk Estimator

Enter your details in the following fields to calculate your risk

Risk Level

Recommendation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is primarily clinical. A slit-lamp examination reveals engorged deep episcleral vessels that do not blanch with topical vasoconstrictors. Laboratory work-up targets systemic associations and may include CBC, ESR/CRP, rheumatoid factor, ANA, ANCAs, and syphilis testing.8 B-scan ultrasonography helps detect the characteristic "T-sign" of posterior scleritis, while MRI or CT can delineate posterior extension or orbital involvement.9

Treatment and Management

Non-necrotizing anterior scleritis often responds to oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as indomethacin. If pain or inflammation persists, systemic corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone 0.5–1 mg/kg/day) are added.10 For refractory disease, steroid-sparing immunomodulators—methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate, or cyclophosphamide—are standard.

Necrotizing or posterior scleritis requires prompt, aggressive therapy. Biologic agents targeting TNF-α or IL-6 (e.g., infliximab, adalimumab, tocilizumab) have shown promising results in small studies and case series.11 Infectious scleritis mandates organism-directed antibiotics or antifungals plus surgical debridement if necessary.

Living with Scleritis and Prevention

Because scleritis frequently recurs, patients benefit from close follow-up every 4–6 weeks during the first year after an acute episode, then at least twice yearly thereafter. Adhering to systemic disease management (e.g., rheumatology care for arthritis) lowers relapse rates.12 Wearing protective eyewear during sports or yard work, promptly treating ocular infections, and avoiding smoking (a modifiable inflammatory trigger) are practical preventive steps.13

Latest Research & Developments

Recent studies explore cytokine-targeted biologics and JAK/STAT pathway modulators to quell ocular auto-inflammation. Investigators at the U.S. National Eye Institute are engineering IL-12 family cytokines (e.g., IL-27, IL-35) that down-regulate pathogenic Th17 responses implicated in scleritis and uveitis.14 Parallel clinical trials are evaluating IL-6 receptor blockade (tocilizumab) for refractory necrotizing scleritis, with early reports suggesting improved pain control and scleral stability.15

Recently Published in Peer-Reviewed Journals

American journal of ophthalmology

May 28, 2025

Incidence and Prevalence of Scleritis Subtypes and Associated Ocular Complications in the TriNetX Database.

Spangler MD, Marshall RF, Kirupaharan N, et al.

American journal of ophthalmology

May 27, 2025

Physician Burden and Time Delays in Initiating Immunomodulatory Therapy for Noninfectious Uveitis and Inflammatory Eye Diseases.

Duran MN, Beltran K, Cao JH

BMC ophthalmology

April 7, 2025

Isolated ANCA-associated scleritis successfully treated with systemic rituximab; a case report and review of literature.

Tahavvori M, Fekri S, Hassanpour K, et al.

Next Steps

If you experience severe ocular pain, deep redness, or vision changes, seek care immediately. The most appropriate specialist is a uveitis or ocular immunology ophthalmologist—they have advanced training in systemic inflammatory eye diseases. Referral pathways vary: some patients are sent by their primary eye doctor or rheumatologist, while others self-refer to academic centers. Wait times can be weeks, so asking your current physician to mark the referral as urgent may expedite scheduling. You can also connect directly with the right specialist through Kerbside, which assists in matching patients to nearby experts.

Before your appointment, gather a list of systemic diagnoses, current medications, and previous lab results. Bring sunglasses for post-exam light sensitivity and arrange transportation in case dilating drops blur your vision. For reputable educational materials and help finding eye-care providers, visit the National Eye Institute’s “Finding an Eye Doctor” resource.16