Pterygium

Also known as Surfer’s Eye

Medical Disclaimer: Information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

See our Terms and Telemedicine Consent for details.

Overview

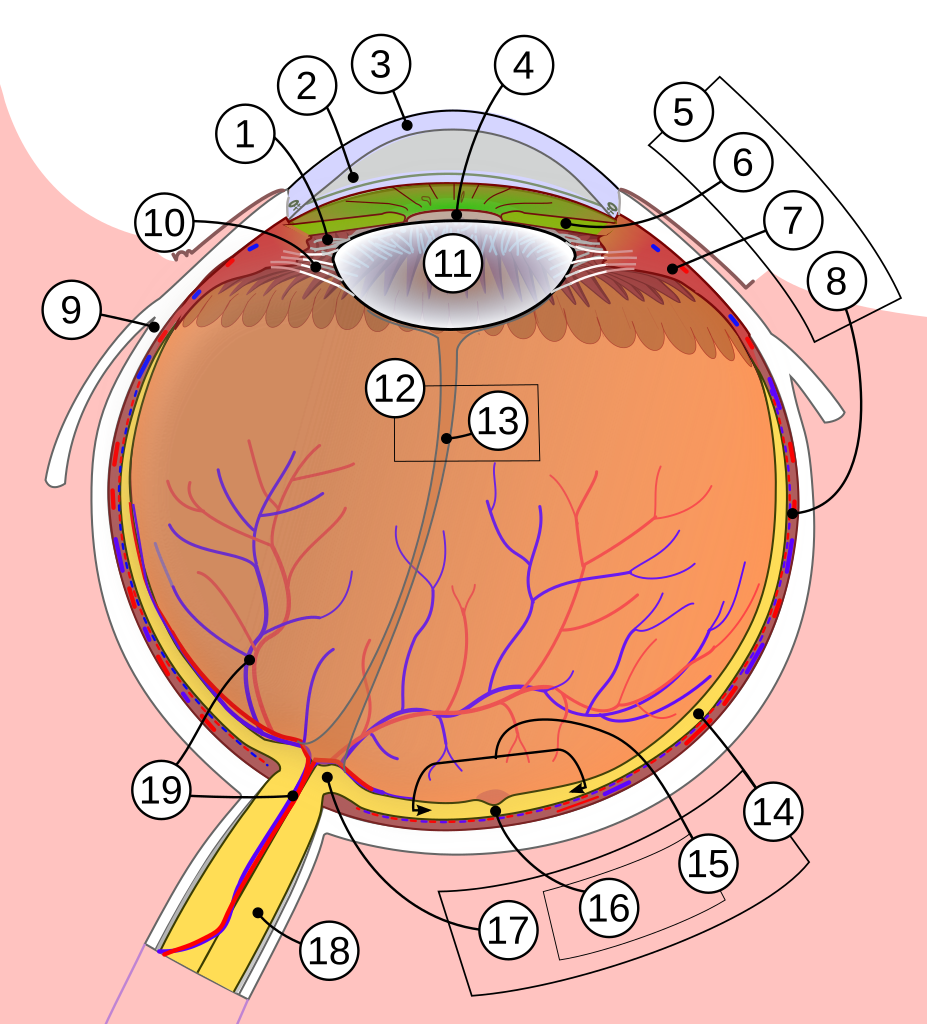

A pterygium is a wing-shaped wedge of fleshy tissue that starts on the clear white surface of your eye (conjunctiva) and can slowly creep onto the cornea, the window you look through. Long-term ultraviolet (UV) exposure, wind, sand and dust irritate the eye’s surface and trigger the over-growth. That’s why the condition is nick-named “surfer’s eye.” Although benign, an untreated pterygium may distort vision or cause chronic redness and irritation. Worldwide prevalence varies widely—ranging from 1 % in temperate zones to more than 20 % in communities near the equator—highlighting the role of sun intensity and outdoor lifestyles.1 Many people never need treatment, but when the growth threatens sight or comfort, surgery removes it and grafts healthy tissue to reduce the risk of regrowth.2

Symptoms

- Visible growth: pink-to-reddish triangular tissue, usually on the side of the eye nearer the nose.

- Foreign-body sensation or gritty feeling—as if sand is stuck under the eyelid.

- Redness and chronic irritation, especially on windy or sunny days.

- Tearing or burning; occasionally dry-eye symptoms when the tear film becomes unstable.

- Blurry or distorted vision if the growth tugs on the cornea or crosses the pupil.

Symptoms often wax and wane. Flare-ups are common after long days outdoors without sunglasses.3 The National Eye Institute notes that adults aged 20–40 who spend significant time in the sun are most at risk, but anyone can develop a pterygium.4

Causes and Risk Factors

The exact trigger is complex, but UV-B light is the prime culprit. Laboratory studies show that chronic UV irritation damages limbal stem cells and sets off a cascade of inflammatory cytokines and blood-vessel growth, encouraging fibrovascular tissue to migrate onto the cornea.

Major risk factors include:

- Living or working within 30° of the equator.

- Outdoor occupations (farming, fishing, surfing, construction).

- Prolonged exposure to wind, dust, smoke or sand.

- A history of dry-eye disease or chronic conjunctivitis.

- Male sex and age > 40 years—probably reflecting cumulative UV dose.

People with light skin and eyes may have slightly higher susceptibility.5 MedlinePlus adds that farmers, fishers and residents of tropical areas shoulder a disproportionate burden because of year-round sunlight and reflective surfaces such as water and sand.6

Pterygium Risk Estimator

Select your details to estimate risk factors.

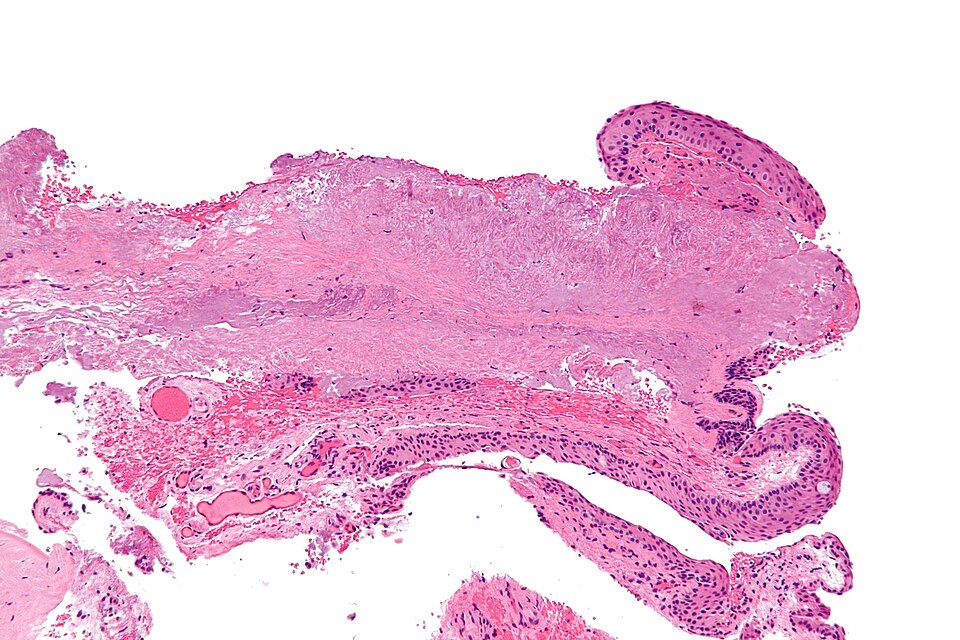

Diagnosis

An eye-care professional can usually diagnose a pterygium during a slit-lamp exam. Key findings include:

- Wing-shaped fibrovascular tissue crossing the limbus.

- Stocker’s line—an iron-deposit line at the advancing edge (seen with special lighting).

- Astigmatism on corneal topography when the lesion pulls the cornea.

Advanced imaging, such as anterior-segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT), helps gauge depth and plan surgery. If a growth appears atypical or very vascular, your doctor may order photographs at regular intervals to monitor change.7 Routine tests are usually unnecessary unless another surface tumor is suspected, as MedlinePlus notes.8

Treatment and Management

Medical therapy focuses on symptom control:

- Lubricating artificial tears or gels 3–4 times daily.

- Short courses of mild steroid drops during flare-ups.

- Topical cyclosporine or lifitegrast for chronic inflammation.

Definitive treatment is surgical excision when the pterygium threatens or blurs vision, induces significant astigmatism, or causes intolerable discomfort. Current gold standard is conjunctival autograft secured with fibrin glue or fine sutures, lowering recurrence to under 10 %. Adjuvants such as mitomycin-C, anti-VEGF injections, or amniotic-membrane transplants are reserved for aggressive or recurrent cases.9 Post-op care includes topical antibiotics, tapering steroids, UV protection and lubricants to foster healthy healing.10

Living with Pterygium and Prevention

Most people can keep a small pterygium quiet with a few simple habits:

- Wear wrap-around sunglasses or photochromic lenses that block 99–100 % of UVA/UVB rays.

- Use broad-brimmed hats and seek shade between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m.

- Apply non-preserved artificial tears before and after windy, dusty or dry-climate exposure.

- Avoid cigarette smoke, which worsens ocular-surface inflammation.

The National Eye Institute specifically recommends sunglasses and hats to lower the odds of developing—or re-developing—a pterygium.11 Cleveland Clinic adds that regular eye exams help track growth and catch vision-threatening changes early.12

Latest Research & Developments

Researchers are dissecting the molecular pathways that drive pterygium growth. Scientists at the National Eye Institute’s NEIBank project have profiled gene-expression patterns showing pterygium tissue carries markers of both corneal and conjunctival cells—opening doors for targeted anti-fibrotic or anti-angiogenic therapies.13 Clinical trials worldwide are evaluating:

- Anti-VEGF eye drops and injections to curb new vessel growth.

- Biologic sealants that shorten operating time and improve comfort after excision.

- UV-blocking contact lenses as a non-surgical option for patients awaiting surgery.

Meanwhile, public-health efforts continue to emphasize inexpensive prevention—good sunglasses and community education—as highlighted by NEI’s corneal-disease resources.14

Recent Peer-Reviewed Research

A Novel Pterygium Beheading Procedure.

Coroneo MT

Clinical outcomes of pterygium surgery over a ten-year period: a review of recurrence and complication rates.

Noguera SI, Nicanor KSA, Ang RET, et al.

Adjuvant Use of Topical 0.05% Cyclosporine A in Primary Pterygium Recurrence Rate: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.

Aleksander-Ivanov Y, Cheidde L, Veiga DM, et al.

Next Steps

If you notice a pink growth spreading toward your pupil, persistent irritation, or new vision changes, schedule an exam with a cornea specialist (a fellowship-trained ophthalmologist who focuses on corneal and external diseases). Many patients start with their regular eye doctor, who can refer urgently if the lesion approaches the visual axis. Wait-times vary, so ask whether photographs and topography can be forwarded ahead to streamline care.

Before the visit, jot down symptoms, triggers and over-the-counter drops used. Bring wrap-around sunglasses—dilating drops may cause light sensitivity. After consultation, surgeons often offer same-day pre-operative measurements if removal is advised. You can also match directly with qualified cornea surgeons through Kerbside’s platform.

Cleveland Clinic notes that early removal, before the pterygium reaches the central cornea, offers the best chance of preserving sharp vision.15 MedlinePlus reminds patients to return yearly for monitoring—even after successful surgery—to catch rare recurrences early.16