Retinitis Pigmentosa

Also known as RP, Rod-Cone Dystrophy

Medical Disclaimer: Information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

See our Terms and Telemedicine Consent for details.

Overview

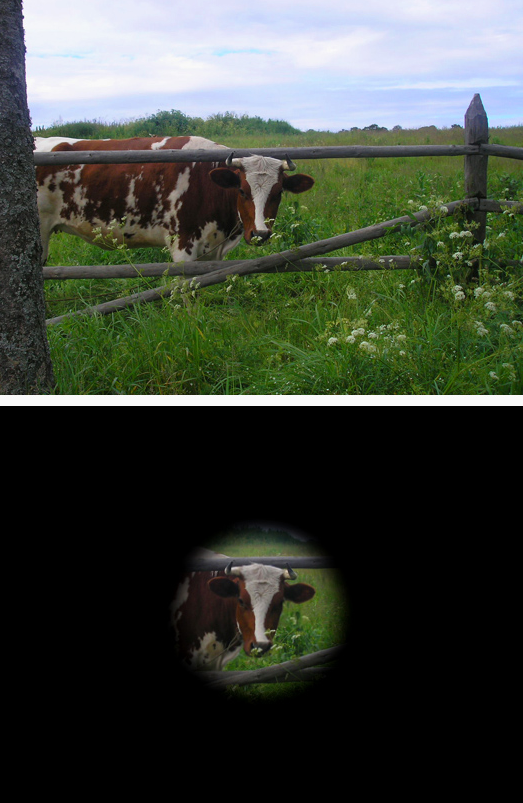

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a group of inherited eye conditions that cause slow, progressive damage to the retina—the light-sensing layer at the back of the eye. Most people notice trouble seeing at night first, then a gradual loss of side (peripheral) vision. Over many years, this can lead to "tunnel vision" and, in advanced cases, central vision problems. There is currently no cure, but many supportive treatments and vision-rehabilitation options can help people live well with RP. 1 RP is one of the most common inherited retinal diseases, affecting roughly 1 in 3,500–4,000 people in the U.S. and Europe. 2

Symptoms

Symptoms usually start in childhood or the teen years and progress slowly. Early on, people often struggle to see in dim light or at night (night blindness). As RP advances, side vision narrows, creating a "tunnel vision" effect. Sensitivity to bright light (photophobia), difficulty with dark-to-light adaptation, problems with color vision, and, later on, central vision loss can occur. 1 3

- Night blindness (difficulty seeing in low light)

- Increasingly narrowed side (peripheral) vision

- Glare or light sensitivity

- Later: challenges with reading and recognizing faces as central vision declines

Causes and Risk Factors

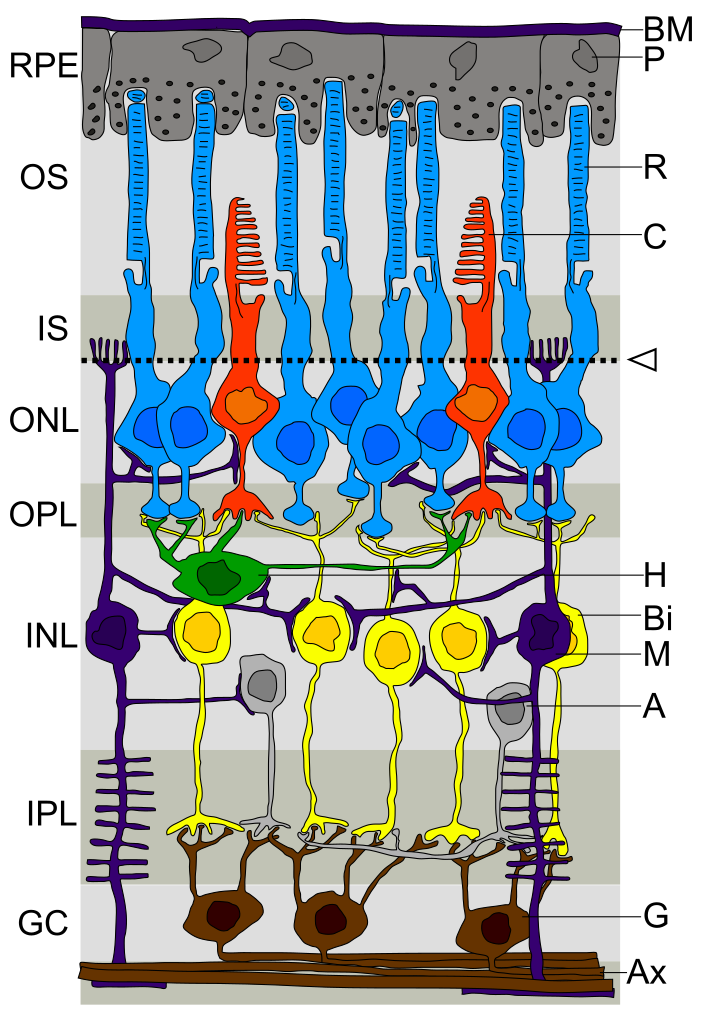

RP is caused by variants (mutations) in genes needed for healthy photoreceptor cells (rods and cones). It can be inherited in different ways: autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant, X-linked, and less commonly as part of a syndrome (such as Usher syndrome, which also affects hearing). Family history is the main risk factor—if a close relative has RP, your chances of carrying a related gene change are higher. Genetic testing can often identify the specific gene involved and guide care and research options. 2 1

RP Risk & Urgency Estimator (for Individuals and At-Risk Relatives)

Select your details to estimate risk factors.

Diagnosis

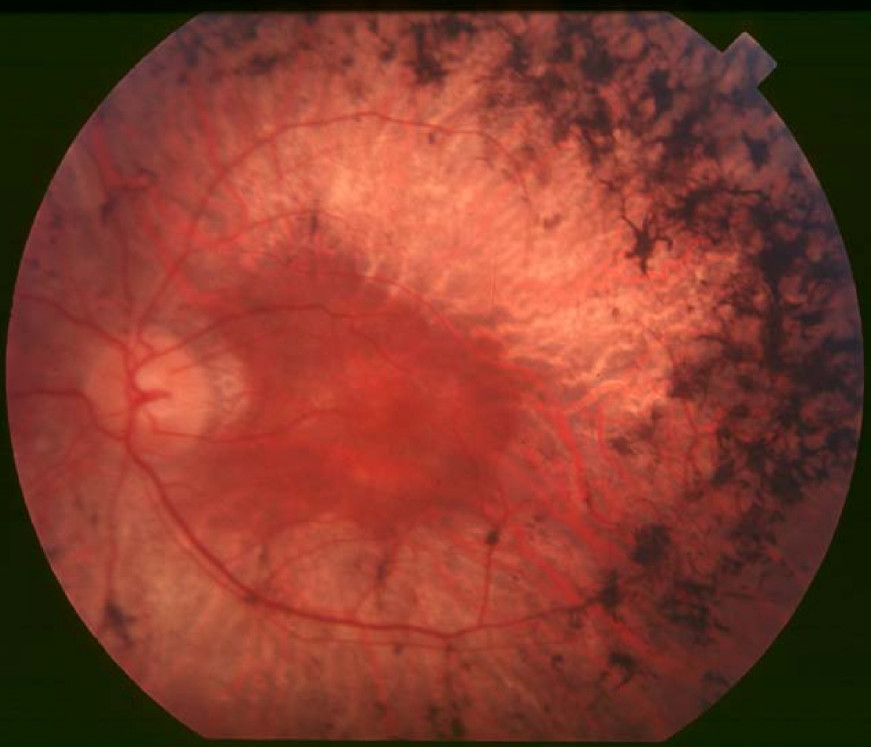

Diagnosis starts with a dilated eye exam and careful history. Classic findings may include "bone-spicule" pigment changes in the mid-peripheral retina, narrowed retinal blood vessels, and a pale optic nerve. Specialized tests help confirm RP and measure progression:

- Electroretinography (ERG): measures the retina's electrical response to light; reduced signals are typical in RP.

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT): high-resolution imaging that shows thinning or loss of the photoreceptor layers and can detect macular swelling (cystoid macular edema).

- Visual field testing: maps side vision loss over time.

- Genetic testing: identifies the responsible gene in many cases and may qualify people for gene-specific trials and counseling.

These tools help determine stage, monitor change, and guide treatment and low-vision planning. 3 1

Treatment and Management

While there is no cure yet, several strategies can help protect remaining vision and improve quality of life:

- Address treatable complications: Cystoid macular edema (CME) can reduce central vision; eye doctors may prescribe drops or pills (often carbonic anhydrase inhibitors) to reduce swelling. Cataract surgery can improve clarity if a cataract forms.

- Low-vision rehabilitation: Magnifiers, high-contrast settings, glare control, orientation and mobility training, and digital accessibility tools help people make the most of their vision.

- Gene therapy (specific situations): The FDA-approved therapy voretigene neparvovec-rzyl (Luxturna®) is available for people with confirmed RPE65-related retinal dystrophy, a cause of RP in some families.

- Vitamins and supplements: A 2023 analysis and a 2024 American Academy of Ophthalmology assessment found no evidence that high-dose vitamin A slows RP progression; vitamin E may be harmful. Do not start high-dose supplements for RP without specialist guidance. 4 5

Research trials are testing new approaches, including additional gene therapies and cell-based treatments (see Latest Research below). Your clinician can help you explore trials and weigh risks and potential benefits.

Living with Retinitis Pigmentosa and Prevention

You can't prevent RP if you carry the gene, but you can reduce risks from avoidable eye problems and plan ahead. Practical steps include:

- Lighting and contrast: Use brighter indoor lighting, task lamps, and high-contrast settings on phones and computers. Sunglasses or tinted lenses can help with glare.

- Home safety: Declutter walkways, add nightlights, label steps, and use high-contrast tape on edges.

- Assistive tech and training: Screen readers, magnification apps, and orientation and mobility training support independence. Ask your eye care team about low-vision rehab services.

- Family planning and genetic counseling: If RP runs in your family, counseling and testing can clarify inheritance patterns and options 2.

- Regular follow-up with a retina specialist helps track changes and manage complications early 3.

Latest Research & Developments

Several promising areas are under active study:

- Gene therapy for X-linked RP (RPGR): Multiple phase 1/2 programs are evaluating adeno-associated virus (AAV) delivery of a healthy RPGR gene. Early-stage protocols and analysis plans are publicly posted, reflecting ongoing clinical development. 6 7

- Retinal progenitor cell therapy: Intravitreal human retinal progenitor cells (jCell) are in clinical trials to assess safety and potential functional benefit for RP. 8

- Better care guidance: Recent expert assessments advise against routine high-dose vitamin A for RP while research continues into gene-targeted and neuroprotective strategies.

If you're interested in research participation, talk with your retina specialist about eligibility, travel demands, and safety monitoring.

Recent Peer-Reviewed Research

Randomized Trial of Biosimilar ABP 938 Compared with Reference Aflibercept in Adults with Neovascular Age-related Macular Degeneration.

Friedman S, London N, Hamouz J, et al.

Founder Homozygous Nonsense CREB3 Variant and Variable-Onset Retinal Degeneration.

Salameh M, Abu Tair G, Mousa S, et al.

Central Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO) complicating post-cataract surgery: a case report and multifactorial analysis.

Xiaodong L, Xin L, Xuewei Q, et al.

Next Steps

If you think you have RP—or you have been diagnosed—seeing the right expert makes a big difference. The best doctor to evaluate and guide long-term care is a retina specialist (ideally one with expertise in inherited retinal diseases). Here's how to move forward:

- Get a referral and records together: Ask your primary eye doctor or primary care clinician for a referral to a retina specialist. Collect prior exam notes, imaging, and any genetic test results.

- Scheduling tips: Retina clinics can be busy. Ask about cancellation lists, telehealth for counseling, and whether genetics consultations are coordinated in-clinic. If you have sudden new floaters, flashes, or a shadow in your vision, tell the office—these could be urgent.

- Prepare for testing: Your first visit may include dilation, imaging (OCT, retinal photos), visual field testing, and sometimes ERG. Plan for a longer appointment and arrange transportation if bright light bothers you.

- Consider genetic counseling/testing: Knowing the gene can clarify family risks and research options.

If you would like help finding the right expert or understanding options, you can connect with a retina specialist on Kerbside for a medical education consult (this is not a patient–physician relationship). We can help you prepare questions, review records, and identify centers with clinical trials.