Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy

also known as PDR

Last updated September 5, 2025

Medical information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

See our Terms & Conditions and Consent for Telemedicine for details.

Overview

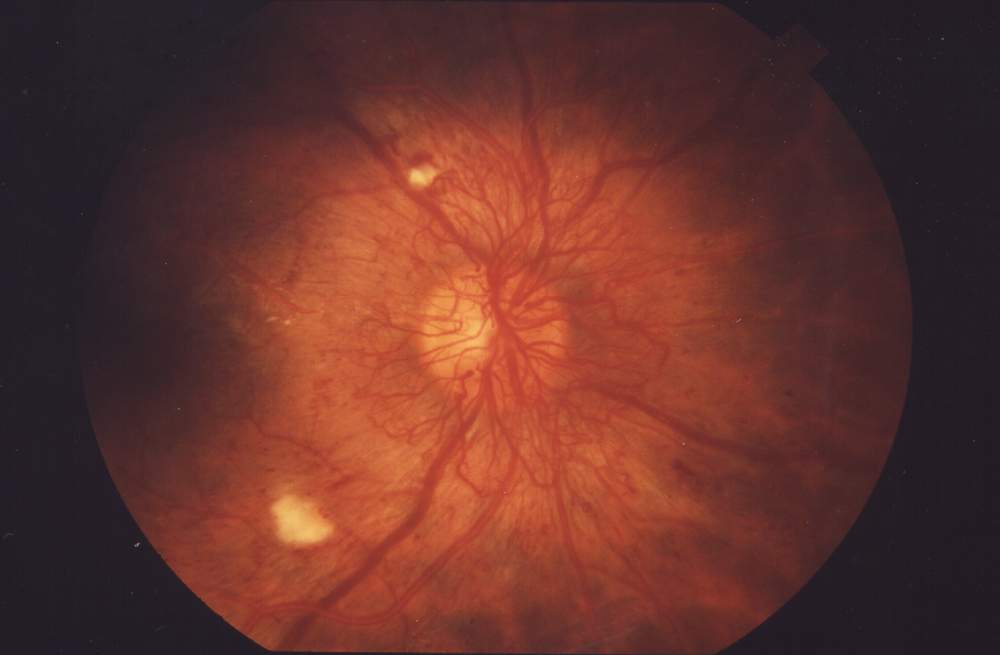

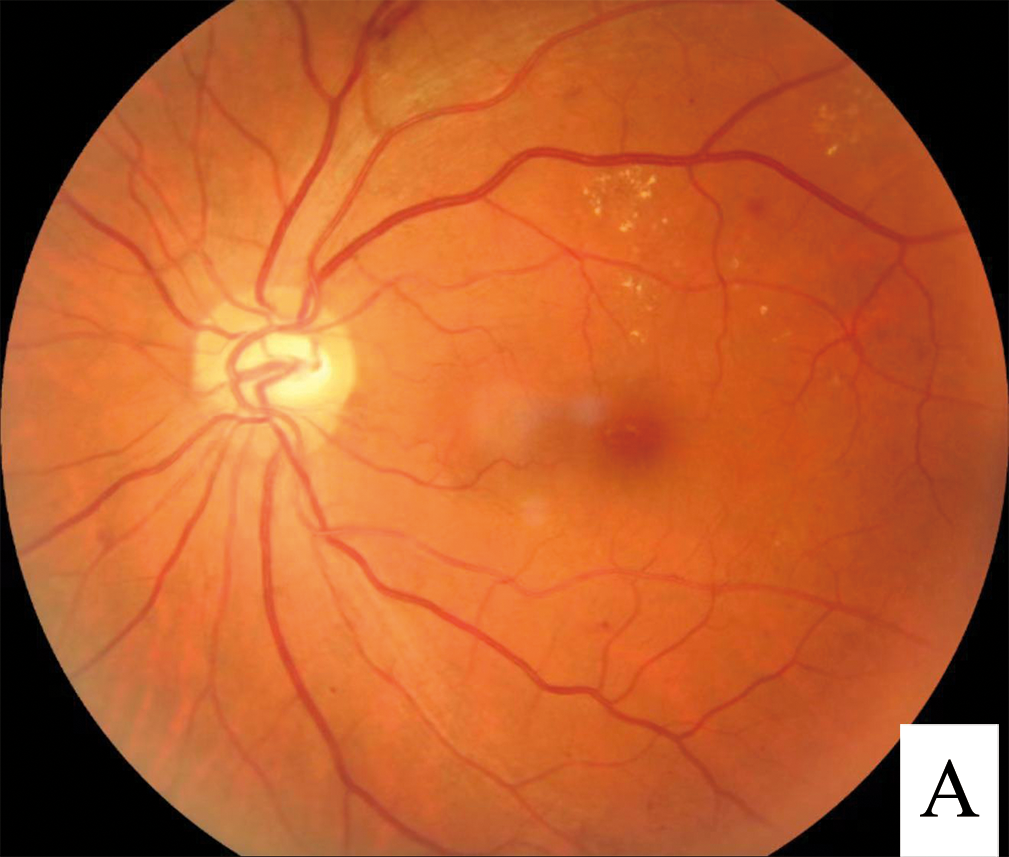

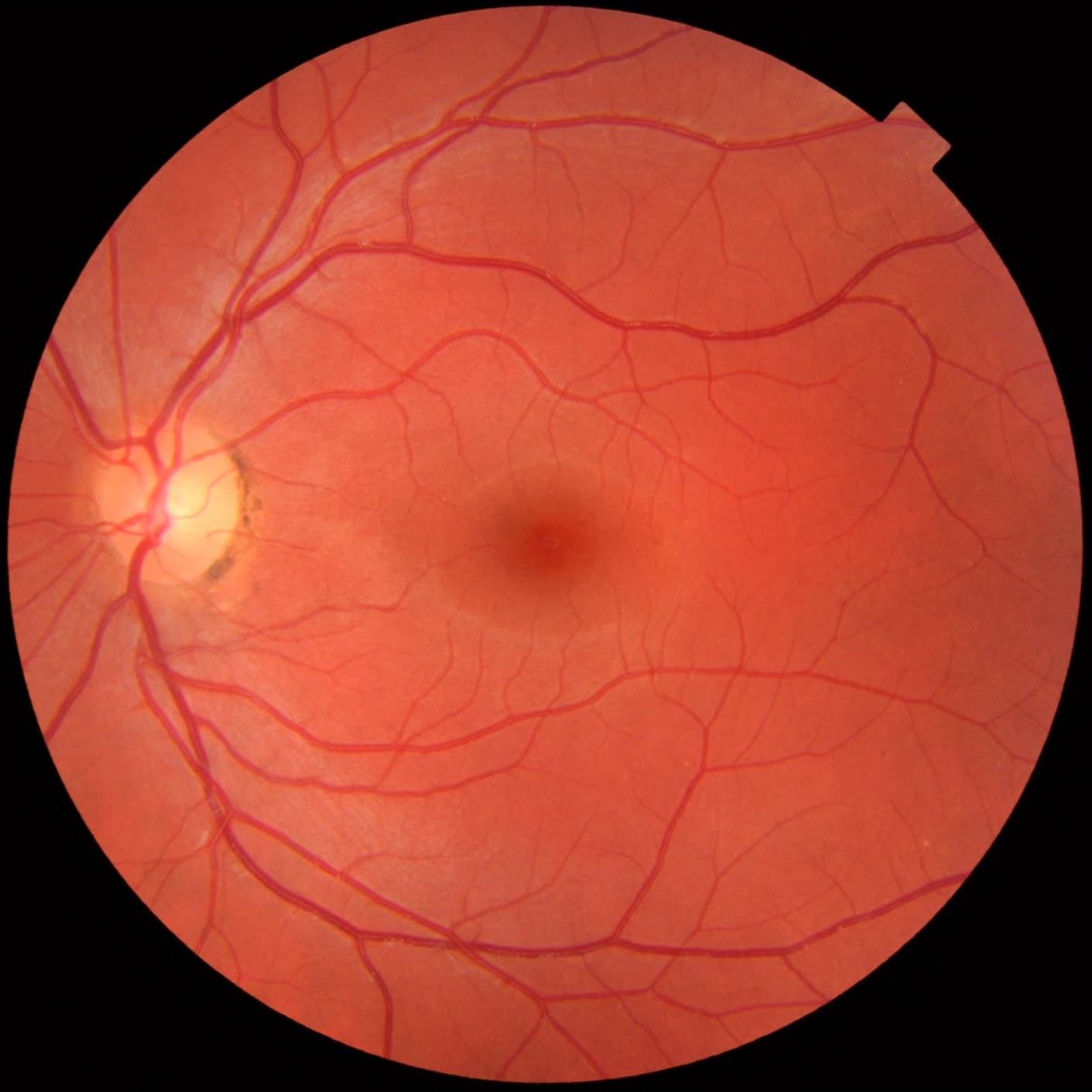

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) is the advanced stage of diabetic eye disease. When parts of the retina do not get enough oxygen, the eye releases signals that cause fragile new blood vessels to grow. These vessels can bleed, create scar tissue, and pull on the retina—threatening sight. PDR can also lead to related problems like vitreous hemorrhage and tractional retinal detachment. Early care can protect vision. 1

Doctors divide diabetic retinopathy into nonproliferative and proliferative. The key difference is the presence of new, abnormal vessels (neovascularization) in PDR. 2

Symptoms

You may not notice symptoms right away. As PDR becomes active, warning signs can include:

- Sudden floaters or dark spots from bleeding inside the eye.

- Blurred or fluctuating vision.

- Dark curtain or shadow (possible retinal detachment—emergency).

Some people have no symptoms until damage is serious. That’s why regular, dilated eye exams are essential if you have diabetes. 1

Causes and Risk Factors

PDR develops when long-term high blood sugar damages tiny retinal vessels. Areas of poor blood flow trigger growth of weak new vessels that break easily and scar. Over time, scar tissue can pull the retina up, causing detachment.

Risks rise with:

- Longer duration of diabetes and higher A1c.

- High blood pressure and high cholesterol.

- Kidney disease, pregnancy, or sleep apnea.

Keeping A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol at goal lowers the chance of severe retinopathy. 3

Enter your details in the following fields to calculate your risk

Risk Level

Recommendation

Diagnosis

An eye doctor (optometrist or ophthalmologist) can diagnose PDR during a complete exam. Typical steps include:

- Dilated exam to look for new vessels on the retina or optic nerve and any bleeding.

- Retinal photographs to document changes.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) to check the macula for swelling.

- Fluorescein angiography in select cases to map areas of poor blood flow and leakage.

Finding neovascularization confirms the proliferative stage. OCT helps track macular swelling, which can occur with PDR. 2 1

Treatment and Management

The goal is to shut down or control new vessels, prevent bleeding, and reduce scarring. Your retina specialist will tailor a plan based on exam findings, imaging, and your ability to keep visits.

- Panretinal photocoagulation (PRP): Laser to the oxygen-starved retina reduces the drive for new vessels; a proven core therapy.

- Anti-VEGF eye injections (e.g., ranibizumab or aflibercept): Block growth signals and can cause rapid regression of neovascularization. In a large randomized trial (Protocol S), ranibizumab was noninferior to PRP for vision at 2 years. 4 Around ~5 years, vision was very good in both groups; anti-VEGF eyes had less visual field loss and fewer macular swelling problems. 5

- Vitrectomy surgery: For non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage, tractional retinal detachment, or dense scar tissue, a pars plana vitrectomy can remove blood/scar and reattach the retina. Outcomes depend on disease severity and overall health. 8

- Systemic care matters: Good control of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol helps treatments work better and last longer. 1

Costs & price (practical tips)

- Laser (PRP): Usually outpatient—request a pre-estimate (clinic + physician fees) and confirm deductible/coinsurance.

- Anti-VEGF injections: Coverage varies; bring your formulary and ask about prior authorization and lower-cost options where appropriate.

- Vitrectomy: Costs depend on facility, anesthesia, and surgeon—ask for a bundled, in-network estimate.

- Visit frequency: Anti-VEGF often starts monthly, then may be spaced out (ask about treat-and-extend).

- Financial help: Manufacturer assistance programs and discount cards may lower copays.

Daily habits that help: Keep appointments, use drops (if prescribed) exactly as directed, avoid smoking, and know your A1c and blood pressure numbers.

Living with Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy and Prevention

PDR is serious, but many people keep useful vision with steady care. Simple steps make a difference:

- Don’t miss follow-ups: New vessels can return; regular checks enable early retreatment.

- Control diabetes and blood pressure: Coordinate with your primary care or diabetes team.

- Call early for changes: New floaters, a dark curtain, or sudden blur need prompt care.

- Protect your eyes during sports or yardwork.

Professional groups stress annual dilated exams for people with diabetes and more frequent visits if retinopathy is present. Screening prevents vision loss. 6

Latest Research & Developments

Anti-VEGF vs. PRP: Ongoing studies compare and combine these options. A recent meta-analysis suggests anti-VEGF therapy (alone or with PRP) can offer short-term advantages in anatomy and vision versus PRP alone, while emphasizing the importance of real-world follow-up. 7

Surgery techniques: Modern vitrectomy uses small-gauge instruments, wide-angle viewing, and sometimes intraoperative OCT to manage severe PDR more safely. 8

Recently Published in Peer-Reviewed Journals

Investigative ophthalmology & visual science

September 2, 2025

Quantifying Choriocapillaris Flow Deficits in Diabetic Retinopathy Using Projection-Resolved OCT Angiography.

Wang J, Hormel T, Park DW, et al.

Ophthalmology. Retina

September 1, 2025

Association of Anti-VEGF Therapy with Reported Ocular Adverse Events: A Global Pharmacovigilance Analysis.

Lakhani M, Kwan ATH, Kundapur D, et al.

Ophthalmology. Retina

September 1, 2025

Macular Buckle, Vitrectomy or combined approach for the management of Macular Hole Retinal Detachment: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis.

Ge JY, Jun Teo AW, Tsai ASH, et al.

Next Steps

If you have PDR—or signs like new floaters, sudden blur, or a shadow—the best specialist to see is a retina specialist (ophthalmologist). Your optometrist or general ophthalmologist can also help and arrange referral when needed.

How to schedule: Ask for a "proliferative diabetic retinopathy evaluation." Bring your glasses or contact details, a list of medicines, recent A1c and blood pressure numbers, and prior eye records. If your insurance needs a referral, call your primary care clinic first.

Timing tips: If the wait is long, request the cancellation list and ask about earlier openings. Mention any recent bleeding, vision drop, or a dark curtain.

Prepare smart: You may be dilated—plan a ride and write down questions about treatment choices, visit frequency, and costs.

For general background on diabetic retinopathy, see the National Eye Institute’s overview. 1

Trusted Providers for Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy

Dr. Emily Eton

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Harvard Medical School

Dr. Grayson Armstrong

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Ophthalmology

Dr. Jose Davila

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

Retina/Vitreous Surgery

Dr. Nicholas Carducci

Specialty

Retina/Vitreous

Education

University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine