Ocular Hypertension

Last updated July 31, 2025

Medical information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

See our Terms & Conditions and Consent for Telemedicine for details.

Overview

Ocular hypertension (OHT) means the fluid pressure inside the eye (intra‑ocular pressure, or IOP) is consistently higher than the normal range of 10‑21 mm Hg, yet there is no detectable damage to the optic nerve or loss of visual field. Roughly 4‑10 % of adults over 40 have OHT, making it far more common than glaucoma itself.1 While most people with OHT never lose vision, the condition is an important warning sign—about 10 % will go on to develop primary open‑angle glaucoma (POAG) within five years without treatment.2 Early identification allows eye‑care providers to tailor monitoring or preventive therapy before irreversible nerve injury occurs.

Symptoms

OHT is often called a “silent” condition because it rarely produces noticeable symptoms. Still, clinicians advise seeking an eye exam if you experience:

- Mild, vague eye discomfort or headache—especially when reading or in dim light.3

- Colored halos around lights or momentary blurry vision—these are uncommon in pure OHT but merit urgent evaluation to rule out acute pressure spikes or coexisting narrow angles.4

Because most people feel perfectly normal, comprehensive dilated eye exams remain the only reliable way to discover OHT early.

Causes and Risk Factors

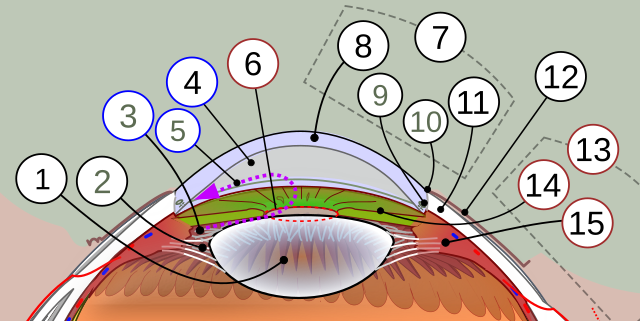

Eye pressure rises when aqueous fluid is produced faster than it drains through the trabecular meshwork. Factors that tip this balance include:

- Age > 40 years, African‑American or Hispanic heritage, and family history of glaucoma—all triple the lifetime risk.5

- Thinner central cornea (CCT < 555 µm), which underestimates the true IOP on Goldmann tonometry and signals weaker connective tissue.6

- High myopia or diabetes mellitus.

- Long‑term corticosteroid use (drops, pills, inhalers, or injections).

- Prior eye trauma or surgeries that disrupt fluid outflow.

OHT can also be transient—seen after sneezing, coughing, or in thick corneas—so multiple readings are required before a formal diagnosis.

Enter your details in the following fields to calculate your risk

Risk Level

Recommendation

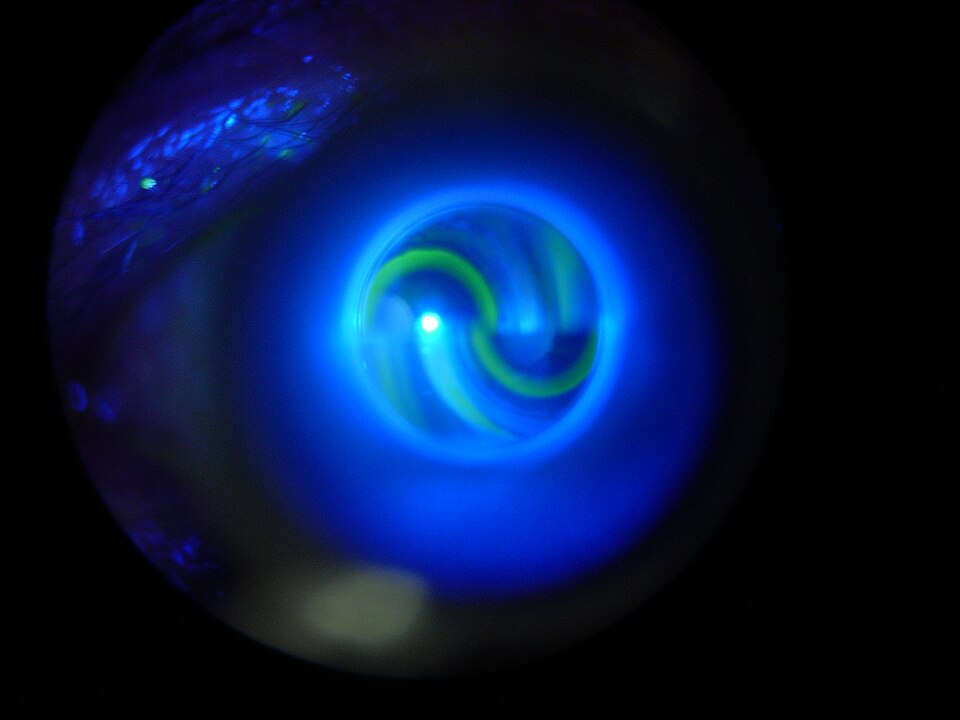

Diagnosis

Establishing OHT involves more than a single pressure check:

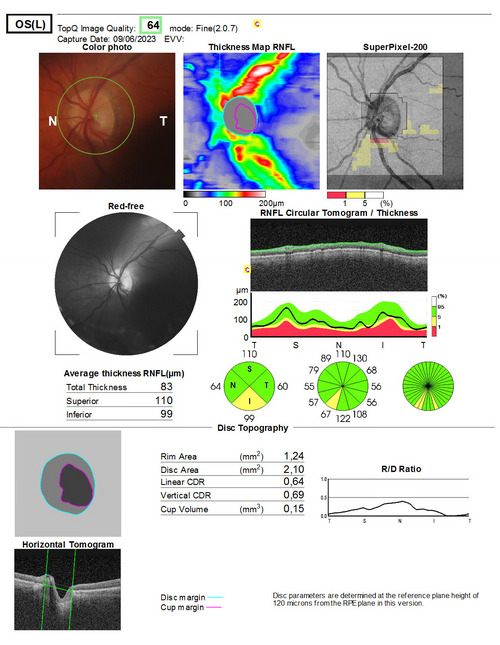

- Goldmann applanation tonometry—the gold standard—averaged over two or more visits.

- Pachymetry to measure central corneal thickness and adjust IOP interpretation.7

- Gonioscopy to make sure the drainage angle is open (rules out angle‑closure risk).

- Optic‑nerve imaging (OCT) and dilated ophthalmoscopy to document a healthy nerve.

- Standard automated perimetry baseline fields—any repeatable defect means the patient already has early glaucoma.

Because IOP fluctuates, some doctors perform diurnal curves or ask patients to self‑monitor at home to catch peak pressures.8

Treatment and Management

The landmark Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS) showed that lowering IOP by about 20 % halves the five‑year risk of converting to glaucoma.9 Management is therefore risk‑stratified:

- Low‑risk eyes (estimated 5‑year conversion < 5 %) usually need observation every 6–12 months.

- Moderate‑risk eyes (5–10 %) often start a once‑daily prostaglandin‑analog drop such as latanoprost.

- High‑risk eyes (10 %+) may benefit from earlier selective laser trabeculoplasty or MIGS (minimally invasive glaucoma surgery) if drops are not tolerated.

After 20 years of follow‑up, OHTS participants who converted tended to have thin corneas, baseline IOP ≥ 26 mm Hg, large cup‑to‑disc ratios, or abnormal visual fields—reinforcing the value of personalized therapy.10

Living with Ocular Hypertension and Prevention

Most people with OHT live normal, active lives. Practical tips include:

- Keep your follow‑up schedule: pressure checks and optic‑nerve scans are painless and quick.11

- Adhere to eyedrops: missing as few as two doses per week can erase the pressure‑lowering benefit.

- Review medications: tell every doctor you see that steroids—even skin creams—can raise eye pressure.

- Heart‑healthy habits: regular aerobic exercise, a balanced diet, and smoking cessation support ocular blood flow.

- Periodic comprehensive exams: the American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends at least every 1–2 years for adults over 40, sooner if additional risks are present.12

Latest Research & Developments

- Genetic insights: Genome‑wide association studies have uncovered more than 120 loci linked to IOP regulation, some now being explored as novel drug targets.13

- Long‑acting delivery: Biodegradable bimatoprost implants and refillable intracameral reservoirs promise months of pressure control without daily drops.

- Artificial‑intelligence risk calculators: Algorithms that combine IOP, corneal biomechanics, and OCT data outperform traditional scoring in predicting conversion to glaucoma.

- Re‑analysis of OHTS data: Investigators confirmed that nearly 60 % of moderate‑risk patients maintained sight without treatment over 20 years, highlighting the safety of watchful waiting in selected cases.14

Recently Published in Peer-Reviewed Journals

BMC ophthalmology

July 24, 2025

Serous retinal detachment with retinal pigment epithelium tear after PreserFlo MicroShunt surgery: a case report.

Sadahide A, Harada Y, Sakaguchi H, et al.

Ophthalmology

July 21, 2025

Efficacy and Drug Interactions of Glaucoma Medications: A Systematic Review and Component Network Meta-Analysis.

Hsia Y, Wang C, Su CC, et al.

American journal of ophthalmology

July 18, 2025

Association between Chronic Oral Nitrate Use and the Risk of Ocular Hypertension and Open-Angle Glaucoma.

Elhusseiny AM, Eleiwa TK, Darwich R, et al.

Next Steps – See a Glaucoma Specialist

If your routine eye exam reveals IOP > 21 mm Hg, ask for a referral to a board‑certified glaucoma specialist for a full risk assessment.15

Scheduling tips: Mention that you have “ocular hypertension with possible glaucoma risk”—most practices reserve slots for these evaluations within 2–4 weeks. If you already take pressure‑lowering drops, bring them to the visit for verification.16

You can also connect directly to the right glaucoma specialist on Kerbside for rapid triage, second opinions, and long‑term care planning.