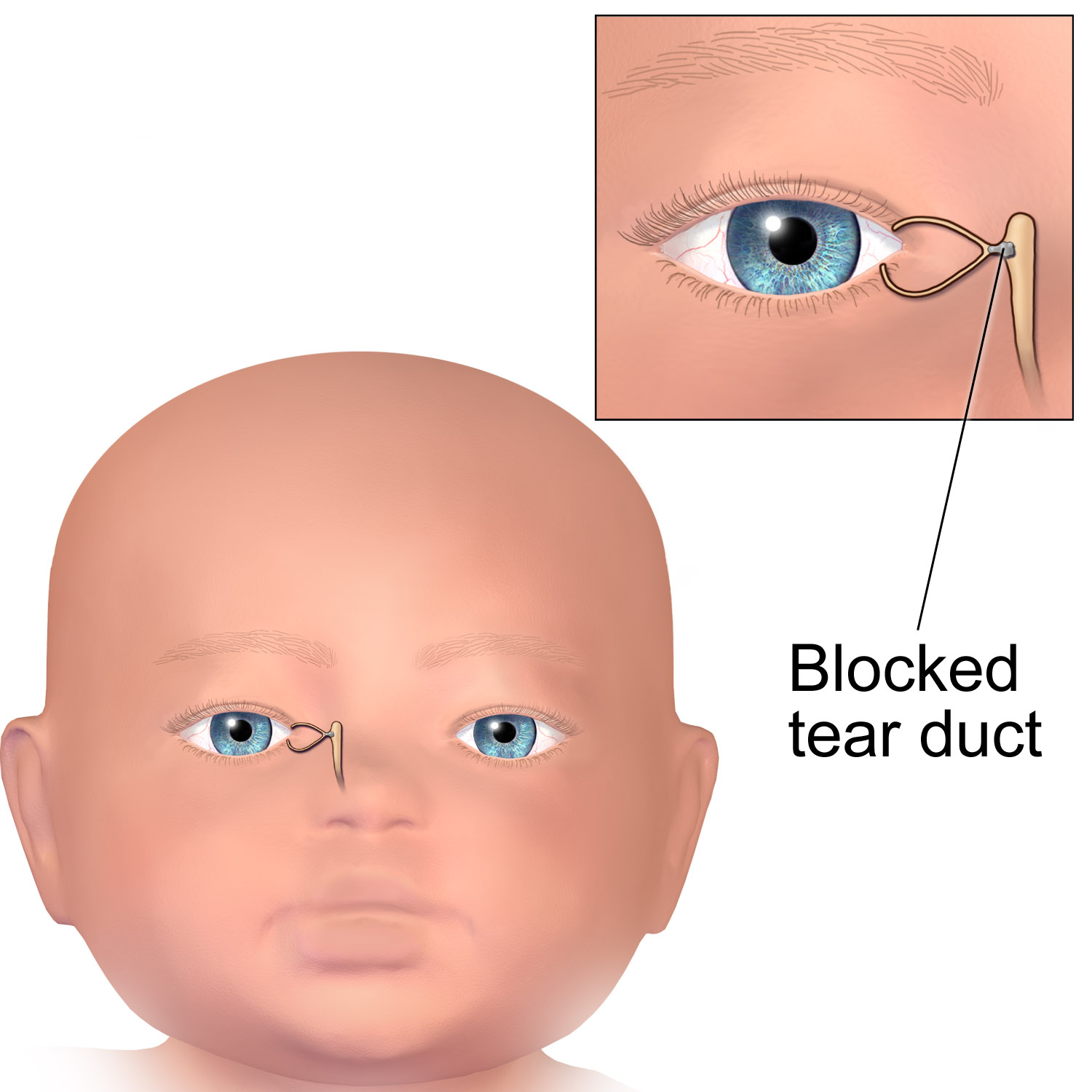

Blocked Tear Duct in Babies

Also known as Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction, CNLDO

Medical Disclaimer: Information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

See our Terms and Telemedicine Consent for details.

Overview

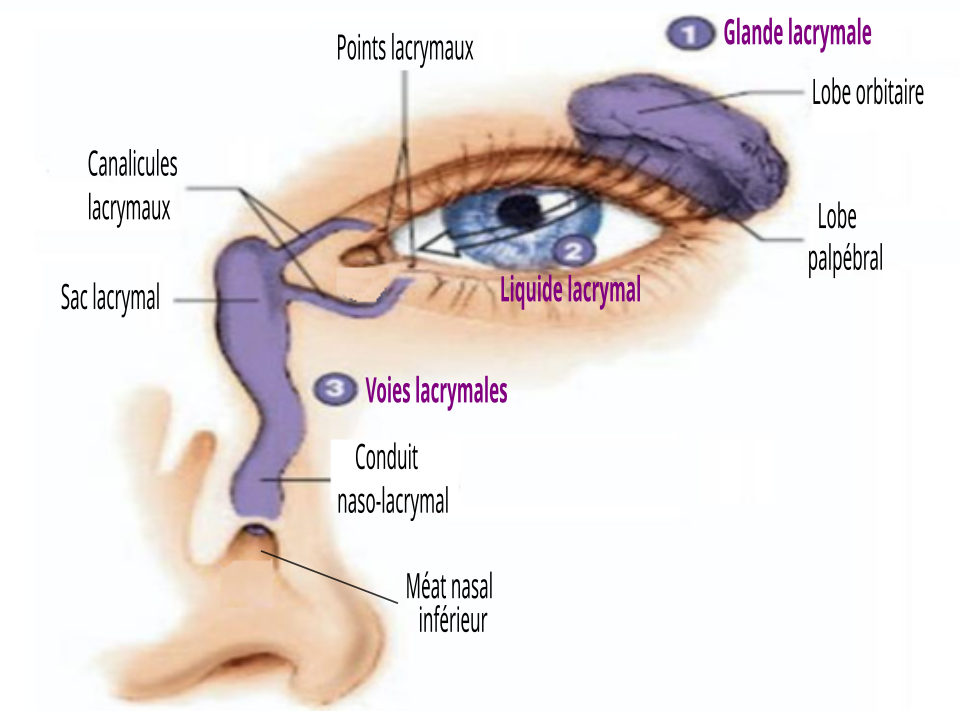

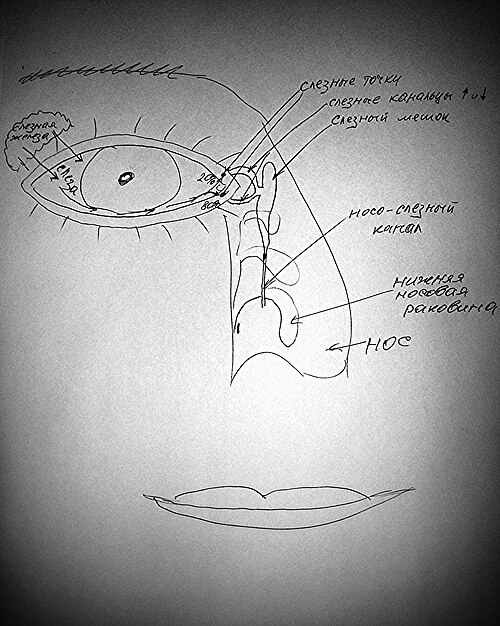

Blocked tear duct — medically called congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (CNLDO) — affects up to 20-30 % of newborns. A thin membrane at the valve of Hasner fails to open before birth, so tears cannot drain from the eye into the nose. As a result, the eye looks constantly watery or develops sticky discharge, even when the baby is not crying.1 The condition is usually harmless and 90 % of cases clear on their own during the first year of life, but persistent obstruction can lead to infection (dacryocystitis) or amblyopia-related blur.2

Symptoms

Parents often notice symptoms within the first few weeks:

- Continuous tearing (epiphora) pooling along the lower eyelid.

- Yellow-white mucus or crusts at the inner corner of the eye, especially after naps.3

- Skin redness from frequent wiping, but the white of the eye stays clear.

- Matting of lashes each morning that improves after warm cleansing.4

- Rarely, swelling below the inner canthus (dacryocystocele) that can cause nasal blockage and noisy breathing.

Because vision is developing rapidly, any new light sensitivity, eyelid swelling, or fever should prompt urgent evaluation.

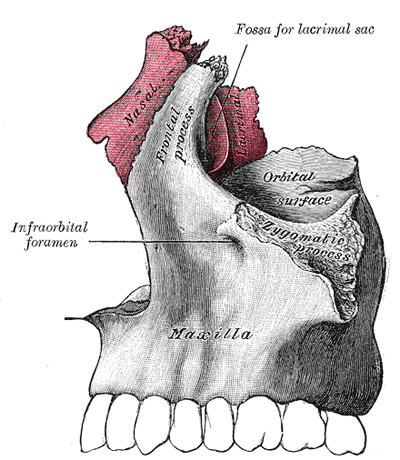

Causes and Risk Factors

CNLDO is usually isolated and sporadic, but several factors raise the likelihood:

- Immature tear-duct canalization — the membrane at the valve of Hasner remains sealed.1

- Prematurity (tear system develops late in gestation).

- Family history of blocked tear duct or mid-facial anomalies.5

- Craniofacial syndromes (Down, Goldenhar, CHARGE) that alter nasal bone growth.

- Birth trauma or forceps delivery causing duct compression.

Contrary to myth, maternal eye drops and breastfeeding practices do not increase risk.

Persistent CNLDO Risk Score

Select your details to estimate risk factors.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is clinical and painless:

- Fluorescein dye disappearance test (FDDT) — dye instilled in the conjunctival sac persists >5 minutes when drainage is blocked.4

- Gentle pressure over the lacrimal sac may reflux mucus through the punctum (“positive ROPLAS sign”).

- Slit-lamp or handheld magnifier rules out conjunctivitis or congenital glaucoma.

- Imaging (ultrasound or CT) is reserved for atypical dacryocystocele, trauma, or failed surgeries.3

A pediatric ophthalmologist will also assess corneal clarity and visual behavior to ensure normal visual development.

Treatment and Management

First-line care is conservative because most ducts open spontaneously:

- Crigler (lacrimal sac) massage — caregivers use a clean fingertip to apply downward pressure from the medial canthus toward the nostril 3–4 times daily, producing a hydraulic pop that can rupture the membrane.7

- Warm compresses and lid hygiene to clear debris.

- Topical antibiotics for mucopurulent flare-ups.

- Probing under brief general anesthesia if tearing persists beyond 10–12 months or earlier if recurrent infections occur; success ranges 80–95 %.6

- Adjunct procedures (balloon dacryoplasty, silicone intubation, or dacryocystorhinostomy) for complex or refractory cases.

Post-operative care is minimal and children typically resume normal feeding and play the same day.

Living with Blocked Tear Duct and Prevention

While awaiting spontaneous resolution or surgery, families can:

- Clean eyelids with sterile saline or warm water several times daily.

- Use preservative-free artificial tears if the eye looks dry between episodes of watering.

- Keep fingernails trimmed and avoid rubbing to reduce skin irritation.

- Follow the 3-step massage routine: wash hands, apply gentle downward strokes, then wipe away discharge.15

- Attend scheduled vision screenings to catch amblyopia or refractive errors early.

There is no proven way to prevent CNLDO, but controlling maternal smoking and treating prenatal infections support overall ocular health.

Latest Research & Developments

Scientists and surgeons are refining care:

- Office-based probing with topical anesthesia shows similar success to operating-room probing in carefully selected 4- to 8-month-olds, reducing cost and anesthesia exposure.6

- Balloon dacryoplasty and monocanalicular stenting improve patency rates after failed probing without additional bone work.

- Bio-absorbable antibiotic–steroid stents are in early trials to maintain duct opening while limiting infection.

- Genetic studies are exploring collagen-matrix variants that may predispose certain infants to delayed canalization.3

Recent Peer-Reviewed Research

Association between congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction and otitis media.

Linaburg TJ, Binenbaum G, Buzi A, et al.

Down syndrome is a risk factor for developing corneal ulcers following nasolacrimal duct stenting.

Marks B, Puente MA

The effect of age on congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction probing and stent intubation outcomes in pediatric Down syndrome patients.

Haraguchi Y, Salem Z, Ghali N, et al.

Next Steps

If tearing and discharge persist beyond 6 months despite massage, or if the eye becomes red and swollen, arrange an appointment with a pediatric ophthalmologist or pediatric oculoplastic surgeon. These specialists can perform probing, imaging, or stenting under child-friendly anesthesia and monitor vision development.7

How to schedule: Your pediatrician can refer you, but many tertiary centers and children’s hospitals accept self-referrals. Kerbside can connect you directly to board-certified pediatric eye surgeons for virtual counseling, second opinions, and rapid in-person procedure booking.