Retinopathy of Prematurity

also known as ROP, Retrolental Fibroplasia

Last updated August 13, 2025

Medical information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

See our Terms & Conditions and Consent for Telemedicine for details.

Overview

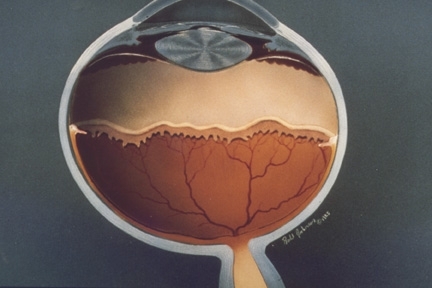

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is an eye condition that affects some babies born early. In ROP, the blood vessels in the back of the eye (the retina) have not fully developed, and they can grow in a disorganized way. Most cases are mild and get better on their own, but severe ROP can lead to scarring, retinal detachment, and vision loss if not treated. ROP is most common in very premature or very small infants cared for in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Early, regular eye screening helps doctors find ROP before it threatens sight 1. In the United States, thousands of babies develop some ROP each year, and a smaller group needs treatment to protect vision 2.

Symptoms

Most infants with ROP do not show obvious symptoms that a parent can see. That is why routine ROP screening in the NICU (or shortly after discharge) is so important. Without screening, severe ROP can progress silently. If ROP becomes advanced, later signs might include abnormal eye movements, a white-looking pupil on photos, or crossed eyes during childhood. These later signs are not specific to ROP, so scheduled eye exams remain the best way to detect and treat the condition early. 1

Causes and Risk Factors

ROP happens because the retina’s blood vessels are still developing when a baby is born early. After birth, changes in oxygen levels and other stresses can disrupt normal vessel growth. This may trigger fragile new vessels that can bleed or pull on the retina. The biggest risk factors are very early gestational age and very low birth weight. Other factors linked with higher risk include fluctuating oxygen levels, prolonged respiratory support, infections, poor postnatal growth, and certain systemic illnesses common in premature infants. 1 Clinical resources also note that extremely low birth weight (often <1500 g) and gestational age <31 weeks carry the highest risk for clinically important ROP. 3

Enter your details in the following fields to calculate your risk

Risk Level

Recommendation

Diagnosis

ROP is diagnosed with a bedside dilated eye exam by a pediatric ophthalmologist or retina specialist using an indirect ophthalmoscope. Doctors document the zone (location in the retina), stage (how far the disease has progressed), and whether there is “plus” disease (enlarged, tortuous vessels in the back of the eye). This system comes from the International Classification of ROP and guides follow-up and treatment decisions. 3 Timing of the first and subsequent exams is based on the baby’s birth weight and gestational age; national guidelines (UK example) recommend screening infants born <31 weeks or <1501 g, with a clear schedule for first and repeat exams to catch vision-threatening changes early. 4

Digital retinal imaging (with specialized cameras) and telemedicine are sometimes used to support evaluation and documentation, but hands-on examination remains the cornerstone of care.

Treatment and Management

Many babies have mild ROP that resolves without treatment. When ROP meets treatment criteria (often called “type 1” ROP), therapy is recommended to reduce the risk of retinal detachment and permanent vision loss. The landmark Early Treatment for ROP (ETROP) trial showed that treating eyes earlier than old “threshold” levels (with retinal ablation) improved outcomes and established modern indications for treatment. 6

The most common treatment is laser photocoagulation to the peripheral avascular retina. In selected cases—especially very posterior disease—anti-VEGF injections (medications that block vascular endothelial growth factor) are used. A Cochrane review of randomized trials found anti-VEGF therapy can reduce high myopia compared with laser, but evidence is limited regarding long-term structural and systemic outcomes; careful follow-up is essential, and practice continues to evolve. 5 Advanced stages (partial or total retinal detachment) may require specialized retinal surgery (scleral buckle or vitrectomy) performed by pediatric retina surgeons.

Living with ROP and Prevention

If your baby had ROP—treated or not—regular eye care through childhood is important. Children born early have higher rates of nearsightedness, amblyopia (“lazy eye”), strabismus (eye misalignment), and reduced peripheral vision. Glasses, patching/vision therapy, and strabismus treatment can help optimize vision. Your care team will guide a schedule for ongoing follow-up after discharge from the NICU. 1

Prevention focuses on safe, careful neonatal care—especially monitoring oxygen levels, supporting steady growth, and preventing infection. Hospitals follow screening protocols so babies at risk are examined on time and referred promptly for treatment if needed. 4

Latest Research & Developments

Research continues to refine how and when to treat ROP. Recent reviews summarize a shift toward individualized care: laser remains time-tested, while anti-VEGF agents (such as bevacizumab, ranibizumab, and aflibercept) may be advantageous in very posterior or aggressive disease but can require longer surveillance for late reactivation and raise questions about systemic exposure. Ongoing trials are studying lower dosing and long-term safety. Shared decision-making that weighs benefits, risks, and follow-up demands is key. 7 High-quality evidence syntheses emphasize that although anti-VEGF can reduce high myopia compared with laser, definitive data on long-term structural and neurodevelopmental outcomes are still limited. 5

Recently Published in Peer-Reviewed Journals

BMC ophthalmology

August 11, 2025

Effect of combined mature cataract surgery and intravitreal ranibizumab injection in eyes with pre-existing diabetic macular edema.

Shen Y, Zhu X, Li AQ, et al.

Ophthalmology. Retina

August 4, 2025

Randomized Trial of Biosimilar ABP 938 Compared with Reference Aflibercept in Adults with Neovascular Age-related Macular Degeneration.

Friedman S, London N, Hamouz J, et al.

BMC ophthalmology

July 31, 2025

Comparative efficacy of photodynamic therapy (PDT), ranibizumab, aflibercept monotherapy, and combination therapies for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Quiroz-Reyes MA, Quiroz-Gonzalez EA, Quiroz-Gonzalez MA, et al.

Next Steps

The best specialist to see: a Pediatric Ophthalmologist (often with a pediatric retina subspecialty) who routinely cares for infants with ROP.

How to schedule: If your baby is still in the NICU, ROP screening is usually arranged by the hospital. Before discharge, ask for the exact date, time, and clinic location of the next eye exam. If your child has already gone home, your pediatrician can refer you directly. Many centers have waitlists; tell schedulers your baby is an ROP follow-up so they can prioritize appropriately. Ask about cancellation lists or urgent slots if the recommended exam window is approaching.

What to bring: your NICU discharge summary, any prior ROP exam notes, and your baby’s current medication list. Plan for dilating drops and a brief period of fussiness. You may be asked to return every 1–3 weeks until the retina is fully vascularized or treatment is complete.

If you’d like help understanding options, you can connect with the right pediatric eye specialist on Kerbside for a medical education consult (informational only; no patient–physician relationship is established).