Keratoconus

Last updated July 24, 2025

Medical information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

See our Terms & Conditions and Consent for Telemedicine for details.

Overview

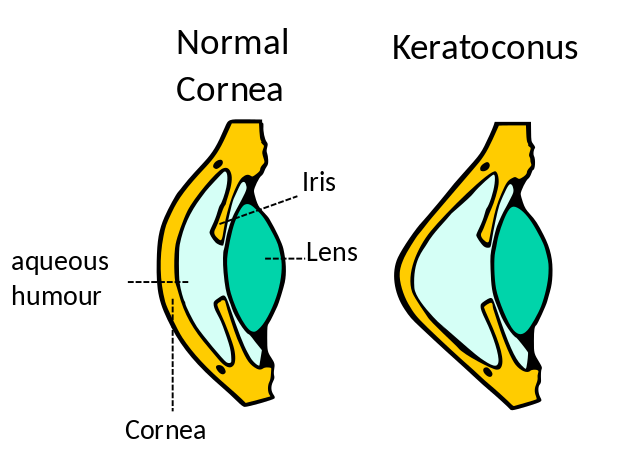

Keratoconus (KC) is a chronic, non-inflammatory disease in which the normally round cornea thins and bulges forward into a cone-like shape. The irregular surface scatters light, causing blurry, distorted vision and glare. Although it usually affects both eyes, severity can differ, and changes typically begin in the teens to early 20s before stabilizing later in life.1 Population-based imaging studies suggest KC is more common than once thought—affecting 1 in 375 to 1 in 2,000 people worldwide.2 Early detection matters: modern treatments such as corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL) can halt progression and prevent the need for corneal transplant when started before scarring develops.

Symptoms

Early KC can masquerade as simple nearsightedness or astigmatism. As the cone steepens, people notice:

- Blurry, ghosted vision (double images or “shadowing”)

- Halos/glare—especially at night

- Frequent prescription changes

- Sensitivity to bright light

- Eye strain or headaches after reading

- Sudden cloudy vision from acute corneal hydrops (rare fluid leak)

Because one eye can mask problems in the other, cover each eye separately during self-checks.34

Causes and Risk Factors

Keratoconus results from genetically vulnerable collagen exposed to mechanical and oxidative stress. Major risks include:

- Family history. First-degree relatives have up to 67-fold greater risk.5

- Chronic eye rubbing—often tied to allergies.

- Atopy (allergic rhinitis, eczema, asthma).

- Connective-tissue or chromosomal disorders (e.g., Down syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos).

- Ethnicity—earlier onset in Middle-Eastern, South-Asian and North-African populations.

- Hormonal surges (puberty, pregnancy).

- Oxidative stress & UV exposure—reduced antioxidant defenses leave corneal collagen vulnerable.6

Keratoconus Risk Calculator

Enter your details in the following fields to calculate your risk

Risk Level

Recommendation

Diagnosis

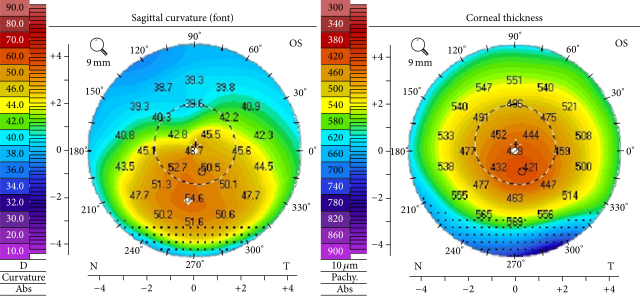

A cornea specialist confirms KC with:

- Slit-lamp exam—thinning, Vogt striae, Fleischer ring.

- Corneal topography/tomography—color maps detect subtle steepening.

- Pachymetry—ultrasonic/optical thickness mapping.

- Anterior-segment OCT or Scheimpflug imaging—3-D curvature and pachymetry profiles.

- Rigid lens over-refraction to rule out lenticular/retinal causes of blur.

Modern devices flag posterior-surface bulges, enabling pre-clinical diagnosis.78

Treatment and Management

While there’s no cure, a step-wise approach preserves good vision in > 90 % of patients:

Optical Correction

- Eyeglasses or soft toric lenses for early disease.

- Rigid gas-permeable (RGP), hybrid, or scleral lenses to mask irregular optics.

Stabilizing Progression

- Epithelium-off CXL: riboflavin + UVA light stiffens collagen, halting progression in ≈ 85 % of cases.9

- Same-day bilateral FDA-approved CXL (iLink®) now available.

Advanced Options

- Intrastromal corneal ring segments flatten the cone.

- Topography-guided PRK + CXL (“Athens protocol”).

- Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty or full-thickness transplant for scarring/extreme bulging.

Widespread CXL adoption has halved transplant rates in many regions.10

Living with Keratoconus and Prevention

Most patients lead active lives with the right tools:

- Control allergies—topical antihistamines or immunomodulators reduce itching and rubbing.

- Hands-off strategies—short nails, cold compresses, rub with knuckle base if unavoidable.

- UV-blocking sunglasses limit oxidative stress.

- Lens care kit—suction cups, saline, backups for travel.

- Regular imaging—every 6–12 months, or every 3 months for rapid growers (teens, pregnancy).

The National Keratoconus Foundation (NKCF) offers peer support and trial listings.1112

Latest Research & Developments

Cutting-edge work is unlocking new strategies:

- AI-driven tomography predicts progression before clinical signs.

- Pulsed and accelerated CXL protocols reduce chair time.

- Transepithelial “epi-on” CXL formulations approach FDA review.

- Tear-film biomarkers & micro-RNAs may enable non-invasive screening.13

- Gene-editing & bioengineered corneal stroma aim to strengthen or replace tissue without grafts.

- Global experts recently issued unified KC staging to harmonize trials and speed approvals.14

Recently Published in Peer-Reviewed Journals

BMC ophthalmology

July 1, 2025

Evaluation of refractive, tomographic and biomechanical changes after customized accelerated corneal collagen cross-linking in keratoconus patients: a retrospective observational study.

Ang RET, Guloy AJA Jr, Cruz EM, et al.

BMC ophthalmology

July 1, 2025

A comparative analysis of the 1-year outcomes of modified Athens protocol versus Cretan protocol in the treatment of progressive keratoconus.

Huang J, Wu J, Xiao W, et al.

American journal of ophthalmology

June 27, 2025

A novel comparative study of inflammatory cytokines through non-invasive tear analysis in children with myopia versus emmetropia.

Nishanth S, Bauer NJ, Shetty R, et al.

Next Steps - **See a Cornea Specialist**

Who to see: Rapid prescription shifts, increasing glare, or allergy-related eye rubbing warrant an urgent visit with a board-certified cornea specialist.

How to schedule: Ask your optometrist or PCP for a priority referral; most centers triage suspected progression within 1–2 weeks. Many academic clinics offer self-referral portals or tele-ophthalmology for out-of-town patients.15

After evaluation, follow the recommended CXL or lens-fitting plan, keep follow-ups, and use support resources—our cornea team is ready to help preserve your sight.