Ocular Melanoma

Also known as Uveal Melanoma, Intraocular Melanoma

Medical Disclaimer: Information on this page is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

See our Terms and Telemedicine Consent for details.

Overview

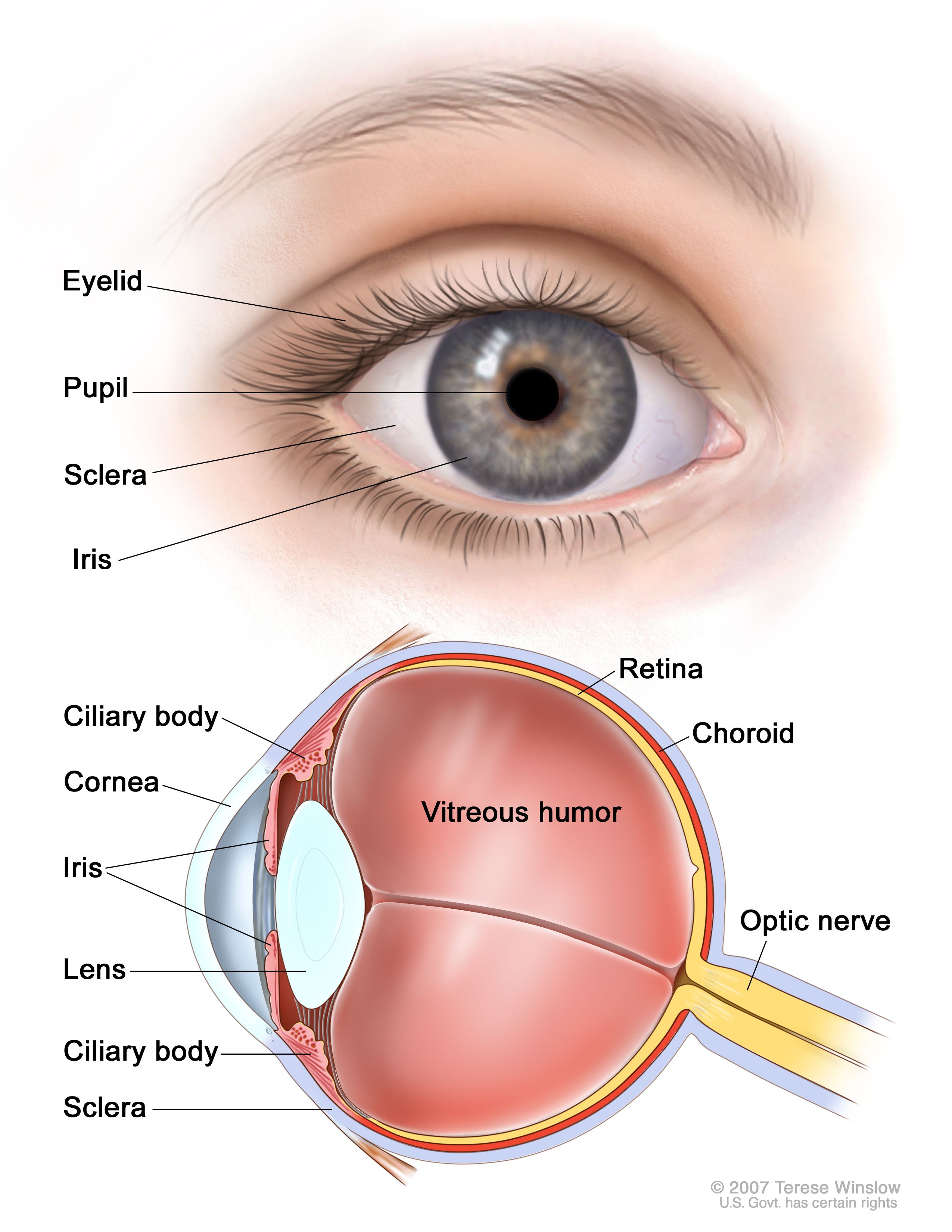

Ocular melanoma is a cancer that starts in the eye’s pigment-making cells (melanocytes). Most cases arise in the uvea—the iris, ciliary body, or choroid—so you’ll often hear it called uveal or intraocular melanoma. It is rare, but it is the most common primary eye cancer in adults. Many tumors are found during a routine dilated eye exam, sometimes before any symptoms appear. Tumor size, location, and whether it has spread guide treatment choices and outlook. Common treatments include eye-sparing radiation (plaque brachytherapy or proton beam) and, for very large tumors or painful blind eyes, surgery to remove the eye (enucleation). 1 2

Symptoms

Ocular melanoma may cause no symptoms at first. When symptoms do occur, they can include:

- Blurry vision, reduced side vision, or new blind spots.

- Flashes or new floaters.

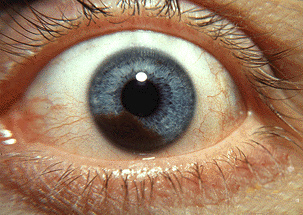

- A growing dark spot on the iris or a change in pupil shape.

- Eye pain or a change in the eye’s position (less common).

Because early tumors can be silent, regular dilated eye exams are important. Seek urgent care for sudden vision changes or new flashes/floaters. 3 2

Causes and Risk Factors

The exact cause isn’t fully understood. Like other cancers, ocular melanoma begins when cells develop genetic changes that let them grow out of control. Some factors are linked with higher risk:

- Light eye color (blue/green) and fair skin.

- Older age.

- White/Northern European ancestry.

- Certain inherited conditions, such as BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome; and rare conditions like oculodermal melanocytosis (Nevus of Ota).

Having any risk factor doesn’t mean you will develop ocular melanoma, and people without risk factors can still be affected. Regular eye exams help catch problems early. 3 2

Ocular Melanoma Personal Risk Snapshot

Select your details to estimate risk factors.

Diagnosis

An ophthalmologist (eye MD) will ask about symptoms and examine your eyes after dilating the pupils. Tests may include:

- Ophthalmoscopy and slit-lamp exam: detailed views of the tumor.

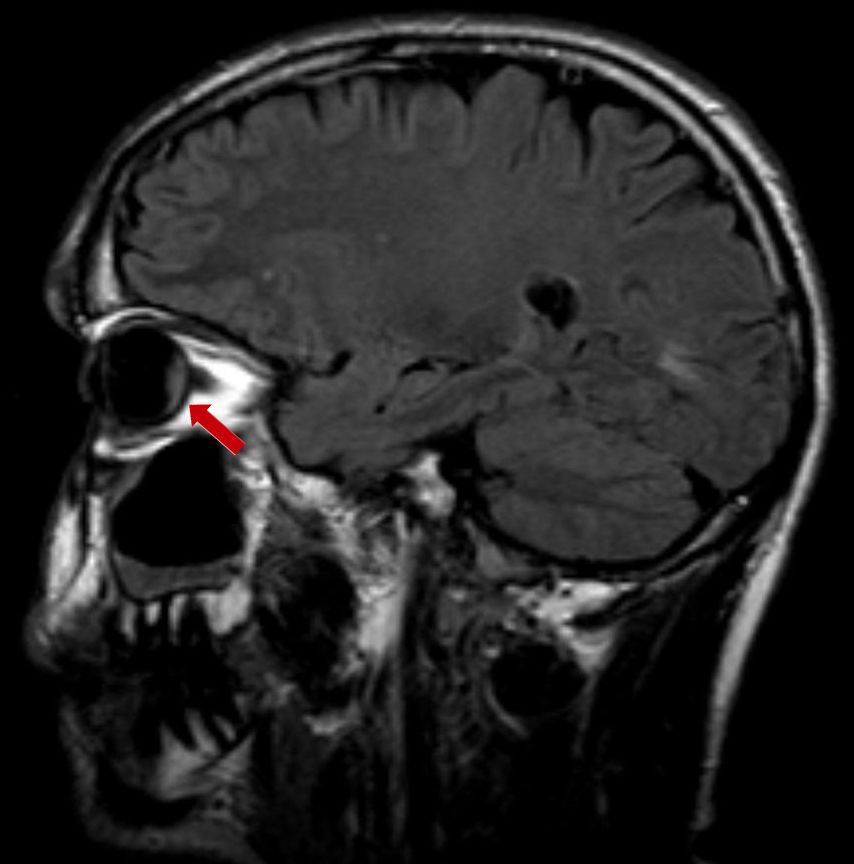

- Ocular ultrasound (A- and B-scan): measures tumor size and internal reflectivity.

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT): cross-sectional images of the retina and fluid.

- Fluorescein or indocyanine green angiography: looks at tumor blood flow.

Most ocular melanomas are diagnosed based on their appearance and imaging, so a biopsy is not always needed. In some cases, a tiny needle biopsy is done to help with prognostic testing. Your care team may also order imaging or blood tests to check for spread, especially to the liver. 2 1

Treatment and Management

Treatment is individualized. Your team will consider tumor size, location (iris, ciliary body, or choroid), vision in each eye, and whether the cancer has spread. Options include:

- Observation (\"watchful waiting\") for very small, stable tumors—particularly iris lesions—when the risks of treatment outweigh benefits.

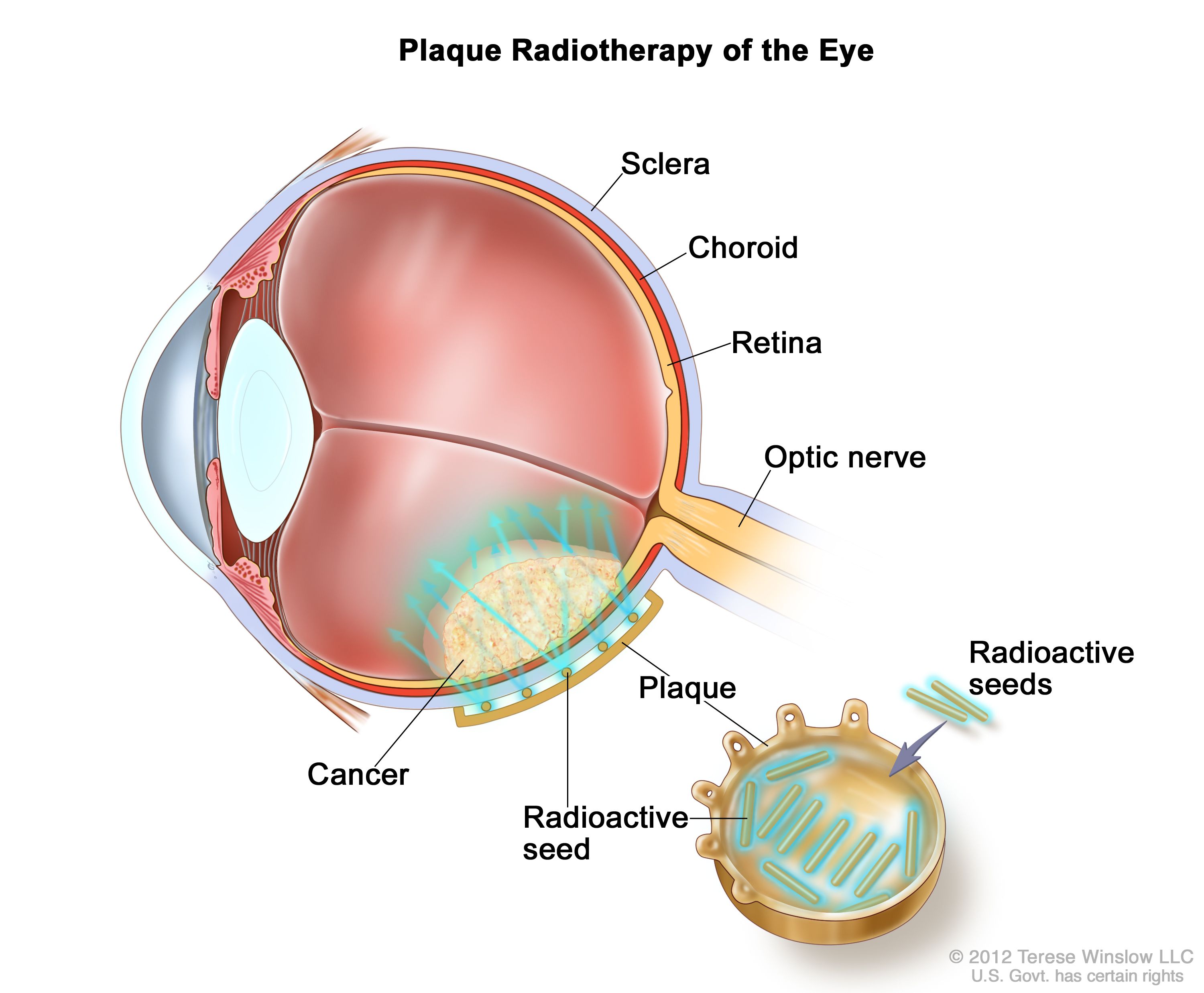

- Plaque brachytherapy: a small gold or steel disc with tiny radioactive seeds is sewn to the outside of the eye over the tumor for several days, delivering targeted radiation to kill cancer cells while limiting exposure to healthy tissue.

- Proton beam (charged-particle) radiation: an external beam option for selected tumors.

- Surgery: local resection in select cases; enucleation (eye removal) for very large tumors, very poor vision, or painful eyes.

Each approach has potential side effects (for example, radiation can affect the retina or optic nerve). Your doctor will discuss ways to protect remaining vision and manage side effects. After treatment, regular follow-up eye exams and periodic imaging—often including liver monitoring—are important. 1

Living with Ocular Melanoma and Prevention

It’s normal to feel overwhelmed. Ask your team about support services, including counseling, low-vision resources, and peer groups. Most people continue daily activities during and after treatment, with adjustments for appointments and eye healing time.

Because some risk factors (like age, eye color, and ancestry) aren’t changeable, prevention focuses on detection. Practical steps include:

- Keep regular dilated eye exams (often yearly)—more often if your doctor recommends it.

- Report new visual symptoms quickly (flashes, floaters, blurring, or a dark spot on the iris).

- Follow your surveillance plan after treatment, including imaging to check for spread, most commonly to the liver.

Your doctor will personalize follow-up based on your tumor’s features and your overall health. 2

Latest Research & Developments

For decades, there were limited systemic options for metastatic uveal melanoma. In 2022, the U.S. FDA approved tebentafusp-tebn (KIMMTRAK) for adults with HLA-A02:01–positive unresectable or metastatic uveal melanoma. In a randomized trial, tebentafusp improved overall survival compared with investigator’s choice therapy. This drug works by directing T cells to attack tumor cells that present a gp100 peptide on HLA-A02:01, so patients need a blood test to confirm this HLA type. 4 5

Clinical trials continue to explore combinations of immunotherapy, targeted therapies, and liver-directed treatments. If you have advanced disease, ask about trials that might fit your tumor features and health goals.

Recent Peer-Reviewed Research

Efficacy of Low-Dose Rate Iodine-125 Plaque Brachytherapy in the Treatment of Uveal Melanoma.

Cernichiaro-Espinosa LA, Choi SL, Taylor Gonzalez DJ, et al.

Survival Outcomes of Uveal Melanoma Involving the Anterior Chamber of the Eye. A National Retrospective Cohort Study: Denmark, 1943-2022.

Nissen K, Ravn Jørgensen AH, Rosthøj S, et al.

Iris Ganglion Cell.

Cummings TJ

Next Steps

If you’re worried about ocular melanoma—or were just diagnosed—here’s what to do next:

- See the right specialist: The best first stop is a ocular oncologist (ophthalmologist with eye cancer expertise). If one isn’t available nearby, a comprehensive ophthalmologist can evaluate and refer you.

- Get your records together: Bring prior eye photos, imaging, and reports. Ask for copies of any ultrasound or OCT measurements.

- Scheduling tips: Many specialty centers use referrals and may have waitlists. When you call, ask about cancellation lists for earlier appointments and whether a telehealth review of records is possible before an in-person visit.

- Insurance and referrals: Check if your plan requires prior authorization to see ocular oncology or to obtain specialized imaging.

- Ask about clinical trials: Your team can help you search open studies that match your situation. 1

You can also connect directly to the right specialist on Kerbside for a medical education consult to learn about options and questions to ask. This is for education only and does not establish a patient–physician relationship.